3 GTM Observations for Q4

A few things on my mind as we prepare for 2026.

Today I want to do three quick hits on topics I’m thinking and reading about as we barrel through the final days of 2025.

Every senior seller started as a junior seller. What happens if AI eliminates all the entry-level jobs?

There’s a software “middle class” and it employs a lot of GTM folks. What if it disappears?

I’m not an economist, but I have lived through a couple massive bubbles. And AI sure is looking frothy these days.

Let’s jump in.

Where will new sellers come from?

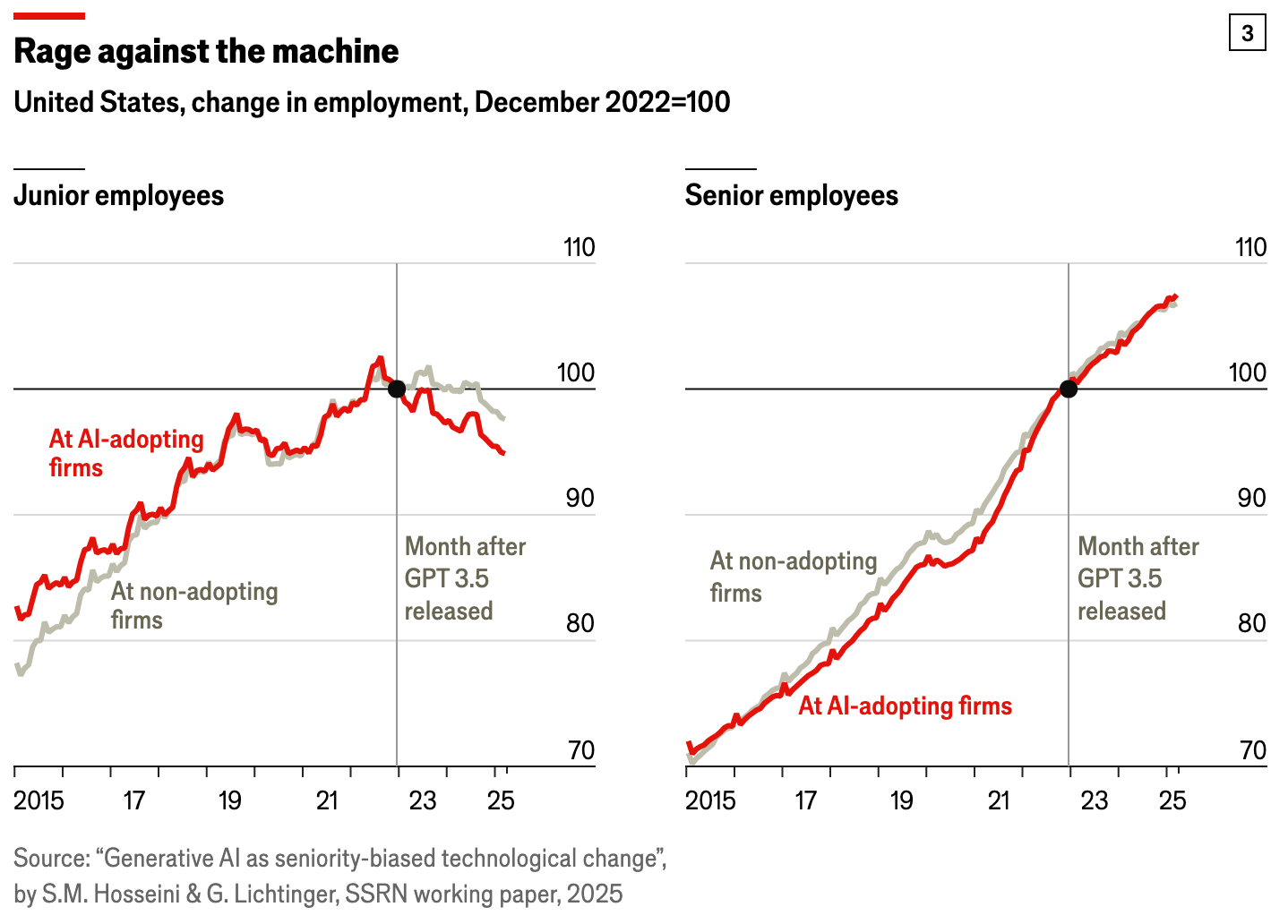

I saw a LinkedIn post earlier this week that featured the chart above. I instantly recognized The Economist house style1 and tracked down the original article with a reverse image search.

It caught my eye because the inflection point at the end of 2022 is wild. Junior roles are disappearing, while seniors aren’t impacted at all (yet).

While the chart itself isn’t specifically about sales, it touches on something I’ve talked about with several sales leaders: if we eliminate all the junior roles (SDRs, etc) that are the typical entry point into a sales career, where do we get the next generation of sellers?

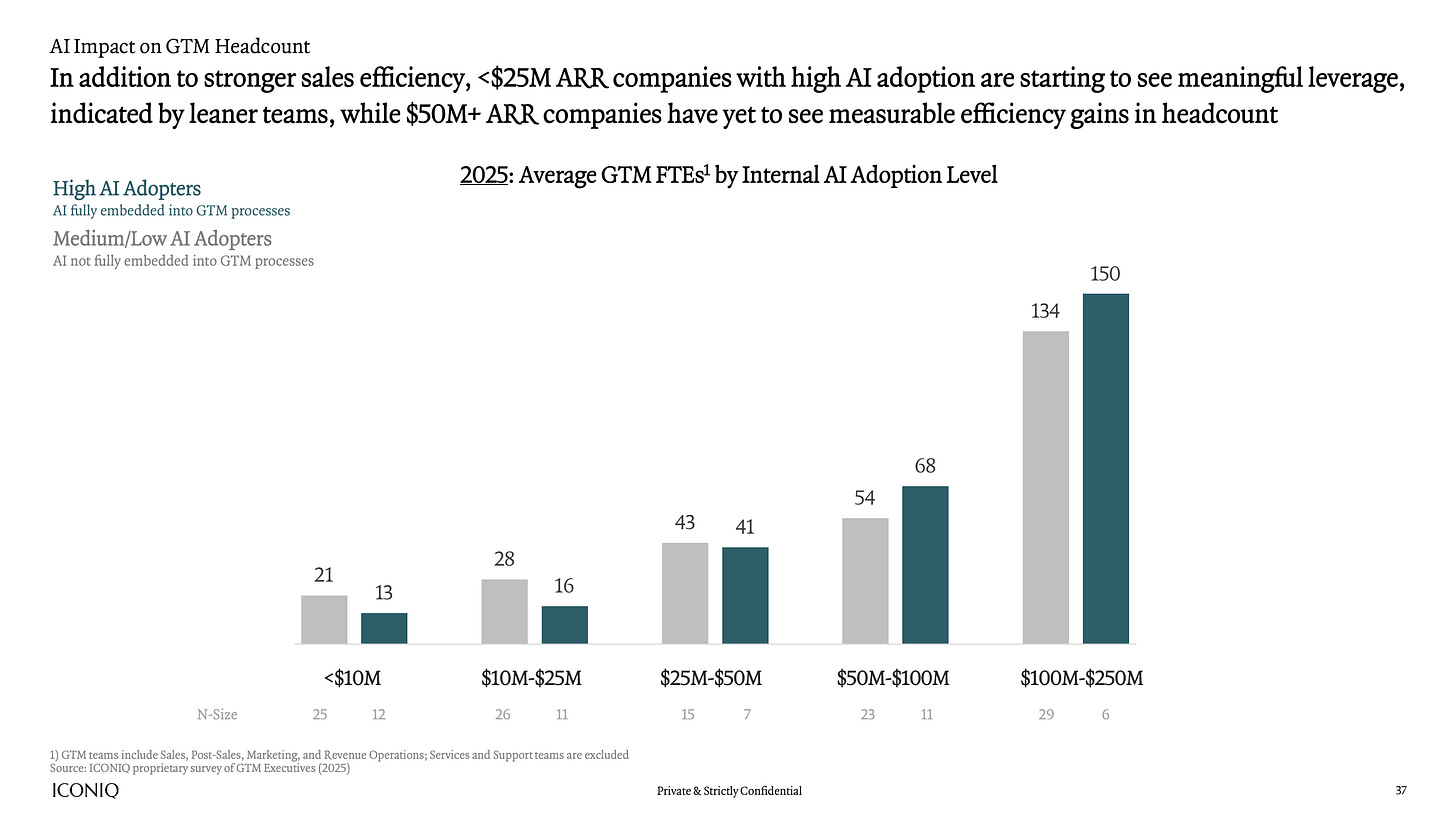

We’ve all heard the anecdotes about smaller sales teams and replacing SDRs with AI, but there’s not much quantitative data (that I can find) which isolates the impact on entry-level sellers. There is however, some data that supports the idea that AI adoption is reducing sales team size overall. And it seems unlikely that this reduction is coming at the expense of productive, senior headcount.

For example, the ICONIQ State of GTM report points to a significant reduction in GTM FTEs for high AI adopters at earlier-stage companies:

These companies are more agile and less able to support high CAC, so of course they’ll press any cost advantage they can find. Could this phenomenon just be because they haven’t yet built the people-heavy teams required for enterprise? After all, a lot of the “no sales team” success stories change their tune later on.2 It could be, but the “High AI” vs “Low AI” differences are pretty stark.

So why does this matter? Sales—in B2B tech especially—is a rare form of white collar(ish) job. It’s historically been a path for someone with plenty of grit but few credentials to break into tech and make a great living. It’s as close as we can get to a role that’s built on meritocracy.

Also, since nobody learns sales in school, it’s also one of the few areas of tech where an apprenticeship model is alive and well. People learn sales on the job from other sales people while they do the crappy work (e.g. cold calling) that more senior people have earned the right not to do.

If we use AI to replace most of those entry-level folks, we’ll lose a meaningful path for economic upward mobility and the “apprenticeship” pipeline that builds tomorrow’s sellers.

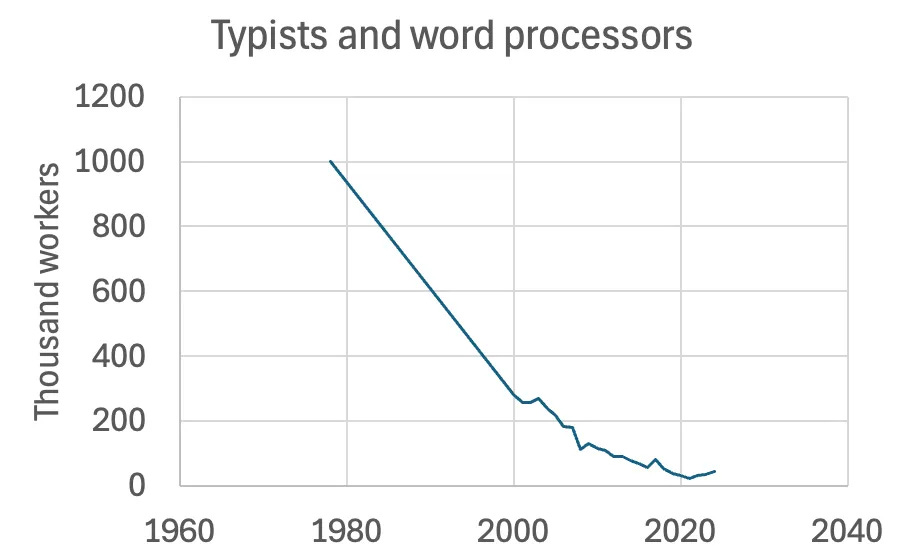

I could be wrong about all this. Maybe the idea of employing entry-level SDRs dialing for dollars will seem as quaint in 40 years as the idea of employing 1,000,000 typists.

One key difference: becoming a human word processor3 in 1980 wasn’t a ticket to potential upward mobility and there were plenty of ways to learn to type without an apprenticeship.4

I think we’ll probably regret losing skilled sellers more.

The death of the software middle class

This week Jason Lemkin5 published an article on SaaStr titled Who Will Buy the SaaS Companies?. The gist is that—once upon a time—if you built a SaaS company to $20M+ ARR with decent metrics, you had something someone would want to buy. Now the mechanisms that fueled this are all breaking down.

I think of the companies Jason describes as the “middle class” of software. They’re more than an indie software developer selling something on an app store, but they’re never going to IPO. They tend to employ quite a few GTM folks.

Unfortunately, that middle class may not be long for this world. All the VC dollars are going to AI while PE is souring on SaaS as the business model starts to look less predictable.

VC Brett Queener wrote a much more substantial treatment of a similar topic earlier this month. He called out the logical implication of the shift:

Except for the absolutely crazy breakout companies, this implies that if you don’t have a ton of committed ARR and a lot of upfront cash payments, you’ll need to fund some of your growth the old-fashioned way — from the balance sheet. […]

I believe it may be more of a winner-take-all approach at some point in each market, as those companies with the most funding are likely able to invest the most GTM opex ahead of growth.

Two things:

Acquisition is the hardest problem in startups and it’s not even close.

It’s very hard to self-fund acquisition without lucking into either a market wave or some kind of PLG viral loop. I bootstrapped my last startup, so I know about funding acquisition from the balance sheet. It’s a rough math problem in the best of times and only gets harder if you’re using month-to-month contracts to lower the barrier to entry.

If you extrapolate from both Jason and Brett’s posts, you can see today’s software industry become an even more extreme winner-take-all environment where 0.1% of companies can raise enough to pay for acquisition and everyone else dies. Take it one step further and it leads to an arms race of VCs picking winners earlier and earlier—basically finding the smartest-looking baby in the maternity ward and handing it a scholarship to Stanford.

It’s hard to see how this wouldn’t lead to fewer surviving software companies. Software would be like legacy industries—capital intensive and difficult to break into. Two guys in a garage just won’t cut it anymore.

Putting this all together, we may see the software middle class disappear. It just won’t be possible to generate a meaningful outcome there. We’ll be left with the capital-heavy winners and the extremely capital light indies.

Something to think about as you look for your next CRO gig.

Come on guys, it’s definitely a bubble

On Tuesday, OpenAI completed its restructuring as a for-profit company. To celebrate, Sam Altman held a livestream which included this little nugget (per The Information):

Altman said OpenAI has $1.4 trillion worth of “financial obligation” from commitments it has made to use or develop 30 gigawatts of data center capacity. However, there’s a large gap between OpenAI’s revenue, which is projected to reach $13 billion this year, and its planned spending on servers to develop its technology and stay ahead of rivals such as Google and xAI.

Now look, I can do math. OpenAI is growing at an insane clip. Today’s $13B in revenue will be a lot more tomorrow. They can IPO now that they’re a “real” company. There are plenty of ways for them to come up with cash. However, the words “large gap” are doing a lot of work up there.

Also, let’s not forget that this restructuring helps unlock a $100B investment from Nvidia (who just hit $5 trillion in market cap yesterday). Gee I wonder who sells the GPUs that $100B will get spent on?

So… that’s great. But I’m sure it gets more sane:

Microsoft said it secured a commitment from OpenAI to spend $250 billion renting Microsoft servers over an unspecified period, mirroring a similar commitment OpenAI recently made to rent servers from Oracle.

Oh.

Microsoft, by the way, now owns 27% of OpenAI’s new public benefit corporation, a stake that’s worth about $135B. That $250B commitment from OpenAI represents 3.3x Microsoft’s entire 2025 Azure revenue.

I see.

There sure is a lot of money flowing around in a circle here. At least nobody’s loading up on any kind of risky debt to finance all this. Oh, wait. I’m sure it’s fine.

At least we’re doing our part at Gradient Works.

The red and black graphics with the too-clever headline that only works if you imagine it delivered with dry British wit. That’s the stuff.

Some just keep lying about it.

“Human word processor” would have sounded redundant in 1980, kind of like “human seller” would have in, say, 2021.

There are plenty of reasons for this, not the least of which is that those jobs were female coded with a pretty clear ceiling put on them.

Or whatever AI entity writes his content.

This article comes at the perfect time, realy appreciate you diving into this. The impact on junior dev and teaching roles is also getting wild.