Build or Buy?

The question has never been more pressing for GTM teams.

I’m in the midst of a week-long northern swing to visit customers, prospects and smart GTM folks. First up, Boston. In typical Boston fashion1 it gave me a rude welcome with an umbrella-maiming nor’easter. Luckily the conversations were better than the weather.

One of the most interesting conversations was with a VP who runs a large (300+ person) sales org. They’re building their own in-house AI agent capabilities to research accounts and deliver talking points to reps. It’s working so well he believes they’ll be buying a lot less 3rd party software in the future. That led us to discussion of the age-old question of build vs buy.

That question feels especially pressing in GTM because AI is rapidly changing our conception of the technology platform our teams need. The old tools don’t seem quite right anymore but it’s impossible to sift through all the new tools and their claims. And that’s before asking if we even need separate tools. Can AI just do it all somehow?

I’ve dealt with this from both sides of the table in my career: as a RevOps leader (with a reasonable-sized dev team at my disposal) and as a vendor.2 I’ve also personally built quite a bit of software, so I know what it means to create, maintain, improve and otherwise support an application over the long term.

That’s led me to some pretty strong feelings on the build-vs-buy question. The answer is there is no single answer—context matters. So instead of providing a definitive answer, I’ll share my thoughts on how to arrive at the right answer for your particular situation.

Your revenue platform is a product and RevOps is the PM

First, I’m well aware that RevOps does many things—forecasting, comp, process design, sometimes even enablement—that are only tangentially related to the tech stack. But in modern sales, the tech stack sits at the core of how GTM teams operate. That means many RevOps teams own a sprawling set of interconnected GTM systems.

Their job (from a tech stack perspective) is to provide a product to the company as a whole: a platform the GTM org can use to sell. Viewed through that lens, a core RevOps competency is product management of the revenue platform.

They must understand user needs, prioritize those needs, work with stakeholders to build a roadmap, resource that roadmap, deliver the roadmap, and repeat.

Sometimes a big customer (e.g. the CRO) demands something that requires shaking up the roadmap and deprioritizing things that other people (e.g. the SMB reps in Cleveland) need. Sometimes there’s a set of random, (seemingly) unrelated complaints that collectively point to a feature they realize needs to exist but that no one quite knows how to ask for3.

In short, product management.

It doesn’t always seem like product management. RevOps is usually seen as a systems integrator. After all, the GTM tech stack probably starts with a CRM that has a bunch of other off-the-shelf tools plugged into it. In reality this isn’t all that different from other software products—nobody builds their own database from scratch to make their SaaS product—it’s just more obvious because Salesforce has a UI meant for non-technical people.

Some things are definitely not systems integration. There is plenty of functionality that’s so specific and so custom that we build and maintain it in-house. That’s always been the case. But now the build option has become especially prominent. It’s also become closely intertwined with the emerging GTM Engineer role.

That leads us to the question: When do we build something ourselves vs when do we buy something off the shelf?

The meaning of build vs buy

Build vs buy is presented as a binary choice but that’s inaccurate. Building something doesn’t necessarily mean you don’t buy anything—it’s a spectrum. Here’s how I would define the ends of the spectrum:

Build - use internal resources to combine “lower-level” building blocks into a full solution to a problem.

Buy - purchase a solution from a 3rd party that attempts to fully solve the problem directly.

For example, let’s say your problem is that your reps don’t have tailored talking points on calls and that’s hurting your win rates. You could do one of the following:

Set up web scraping infrastructure on AWS, combine scrapers with AI (sourced from the OpenAI API) to direct their behavior while shaping their output, manage the process of running those scrapers, set up tooling to get those outputs into CRM and build out a way for reps to see the talking points.

Buy a product which provides a simple way to define regular scrapes using AI prompts that also integrates with CRM. Provide it with AI prompts, feed it account lists regularly, and sync that data back to CRM.

Get a copilot vendor that monitors assigned accounts and delivers updated talking points in a rep-friendly UI.

Option 1 is obviously the most pure “build” of the three options. Option 2 is still more on the “build” end of the spectrum even though it involves buying a product. That product, however, is a collection of low-level capabilities that require orchestration to solve any particular problem. Option 3, on the other hand, is firmly on the “buy” end of the spectrum as it involves forking over cash for an end-to-end solution.

The more you’re building, the more you’re ultimately responsible for saying how to do something to produce a useful output. The more you’re buying, the more you’re stating what you need done without worrying about how it happens.4

So how do you decide whether to “own how it works” vs “state what you need”?

Interdependence vs modularity

The late, great Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen is known for his research on “disruptive innovation” which looks at how companies deal with new technologies and changing customer needs. He influenced a generation of business leaders with several books, most notably The Innovator’s Dilemma and The Innovator’s Solution.

There’s a lot to unpack in both books—they’re not your typical quick business reads. I’m going to focus on a couple of chapters in the Innovator’s Solution where he talks about product architecture and how it impacts business performance.

Every product has an architecture. The revenue platform is no different. Here’s how Christensen defines it:

A product’s architecture determines its constituent components and subsystems and defines how they must interact—fit and work together—in order to achieve the targeted functionality. The place where any two components fit together is called an interface.

These aren’t graphical user interfaces, these are where two parts of a product come together. Think, for example, about a USB-C plug. That’s an “interface” for data and power transfer.

USB-C is what Christensen would call a “modular” interface. There’s a well defined standard and it does everything you want. It gives you data, it gives you power, it’s thin, it’s light, there’s no wrong way to plug it in. If you pick up a USB-C cable, it’s 99.9% likely to do the job because device manufacturers and cable providers and everyone in between have worked out the kinks and standardized on what a USB-C interface should do.

Now, think back a few years to older Apple devices. Remember these guys:

The two on the left weren’t standardized like USB-C. Apple designed them especially for Apple products. Despite what you may think, they didn’t just do that to be annoying and make more money. The state of the art for data and power transfer back 2012—much less 2003—was pretty crappy. Connectors at the time were fragile, slow, fat and had to be plugged in a certain way. They under-served people’s needs. Apple wanted to do better, so they made their own.

Those old Apple connectors are what Christensen would call an “interdependent” interface. If you want to give people a higher-performance, higher-quality experience when the state of the art is pretty crappy, you’ve got to build both sides.

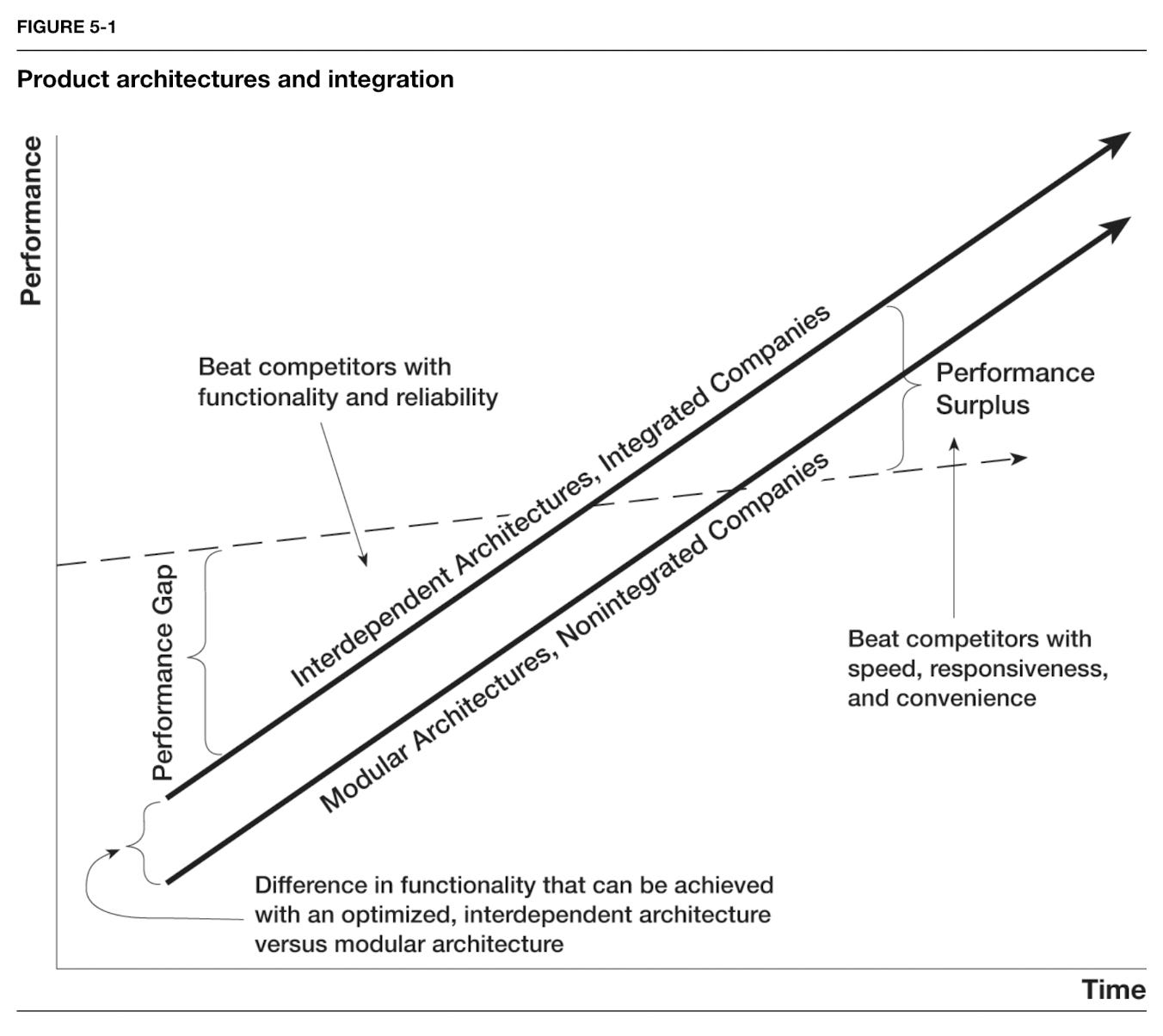

He wraps this whole theory up into a diagram that puts all these ideas together. It’s very HBS professor-y, but it’s worth some study. Here it is:

That diagonal dashed line represents what’s “good enough” performance for customers of a particular product.

When products are immature and aren’t quite yet delivering what customers value, it makes sense to build interdependent product architectures so you can squeeze out every ounce of innovation to get closer to what customers actually want.

As products mature and start becoming more than “good enough”, it’s usually a better business to standardize into modules that get assembled together—it’s cheaper and more efficient that way.

In short, modular stuff will always perform a little worse than interdependent stuff. That matters a lot before most products in a category are “good enough” but basically stops mattering once they are.

There’s one last wrinkle though: what constitutes “good enough” is constantly changing. It might undergo major shifts as customer preferences change or new technologies emerge. When that happens, it starts the whole cycle all over again.

So what does all this have to do with build vs buy?

Let’s apply this to something a little more GTM-specific: sales engagement platforms. Circa early 2022, the innovation of running outbound sequences had evolved to be “good enough” for revenue platform customers (aka the GTM team). SEPs were basically “modules” in the revenue platform. It was a clear buy scenario. You need one of them. Don’t like Outreach? Plug in Salesloft. Or Apollo, doesn’t really matter. Not as standard as USB-C, but not far off. It’s no coincidence this is when Outreach started to stagnate and Salesloft sold to Vista.

Later that year, ChatGPT launched and the idea of “good enough” for sales engagement started to shift quite a bit. Three years later, we’re still not exactly sure what we want, but we know it’s got to be better than a human running sequences with a few variable replacements. So if you’re the PM for the revenue platform, you can’t just plug in a “module”, you probably need something more interdependent. That probably means build, at least for now.

The above logic, I think, largely explains my VP friend’s assertion that they’re better off building these agents in-house. Until you know what “good enough” is, better to own the how.

But, owning the how comes with a big catch.

Building is way more expensive than it looks

Building the first version of a piece of software is the easy part. That’s always been true, but AI—especially vibe coding—makes this particularly seductive. You can get to an initial working version in hours or days instead of weeks. Why not just build it yourself?

The problem is, it’s a trap. If you make the commitment to build instead of buy, somewhere between 60 and 85%5 of the investment that happens over the lifetime of the software will go toward support, maintenance and enhancement.

Are your internal resources equipped to answer questions, track bug reports, fix those bugs, deliver enhancements, test new capabilities? Are they ready to do that for the entire useful lifetime of the software while also managing the rest of their responsibilities? Are they ready to adequately transfer knowledge to another person when they leave to make sure everything keeps running smoothly?

There’s a cost to all that, but it’s often hidden. It’s locked away in other projects that don’t get done, bugs that don’t get fixed and features that don’t get implemented.

External vendors do this full-time all day every day. They’re fixing bugs and constantly incorporating things they learn from others. In most cases, that means the software gets better without you having to a lift a finger. These costs, however, show up on the invoice.

Before you make the decision to build, just make sure you’ve done a thorough accounting of the total cost involved.

Wrapping up

AI has thrown many parts of our tech stacks and revenue platforms into a new world. This technology shift has changed what constitutes “good enough” for our GTM teams, moving us from a cycle of modularity to one of interdependence in the revenue platform architecture.

That’s temporarily shifted the build vs buy equation, pushing more RevOps teams into build territory as they figure out what this new world looks like. That may be the right call for your context. Don’t make those decisions lightly, though. They cost a lot more than you think.

I kid. Sort of…

I don’t much like the word “vendor” since it’s almost always used as a pejorative. Not only does it sound like I’m just out here shamelessly hawking my wares, it kinda sounds like I’m just dispensing it from a machine. I hope it’s at least one of those cool Japanese ones.

Cue Henry Ford’s “faster horse” quote. He probably never said it, but it feels true.

This kind of “hiding the details” is an important part of building software. If we couldn’t do it, we’d all go crazy.

An old source and a newer source.