SaaS Sellers Must Share the Risk

Time to go all in.

Up until 2020 or so, B2B SaaS was simple. Automate a workflow, collect some data and boom you’ve got a system of action or a system of record. Sell the prospect on an ROI model, sign a 1-3 year contract, do some onboarding, do some QBRs and collect the renewals. (Oh yeah, and raise prices 5% a year.)

This worked pretty well in a world of relative B2B software scarcity. There was a ton of low-hanging fruit in the form of manual workflows that were time consuming and expensive but not actually all that complex. Best of all, solving those problems had material productivity benefits and ROI.

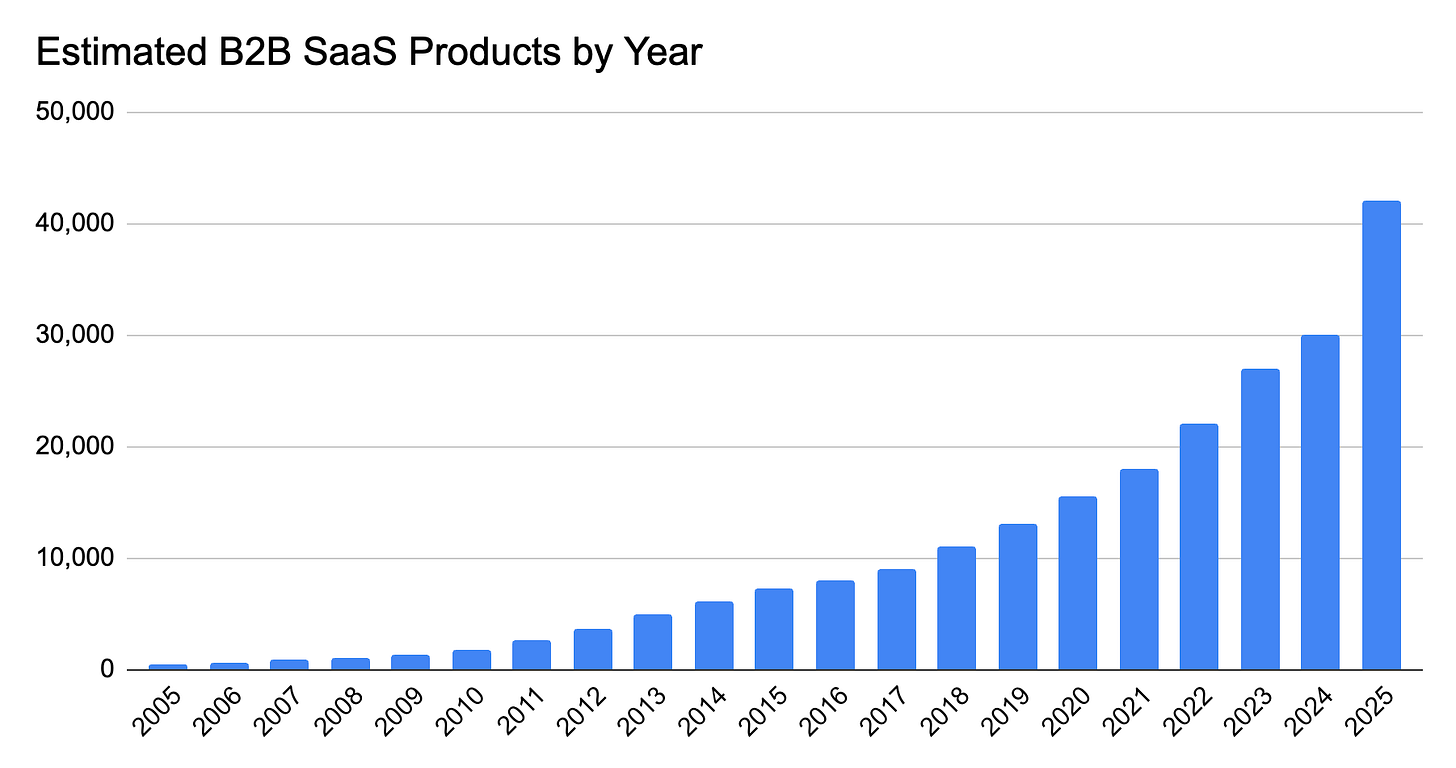

Somewhere along the line, though, I suspect the supply of SaaS products caught up with the demand for solutions. How could it not? Just look at this chart:1

In a world of relatively scarce solutions, vendors had leverage, even if it it didn’t always feel like it.2 SaaS sales teams could play a fun and highly lucrative game. They could sell an outcome while transferring huge chunks of the risk of achieving that outcome to the customer.

That risk took the form of a 12 month (or much longer) commitment combined with taking on most of the cost of actually implementing and managing the software.

Vendors helped with implementation, but it often came with implementation fees or 3rd party integration partners. Ongoing management of the software rested with the customer which meant retraining existing resources or hiring new roles—not to mention any ongoing technical care and feeding required to keep up with vendor changes.

Just think about the canonical SaaS category: CRM. Salesforce sells an outcome—a wildly more efficient sales team. The customer pays them handsomely for that. But very few people just stand up Salesforce (or even Hubspot these days) without paying an implementation partner and paying someone on staff to manage it on an ongoing basis. All this commitment before any proof of the promised benefit.

CRM is an old school example, but most any non-PLG3 B2B SaaS has similar dynamics. I don’t see how that can continue. In the post-ZIRP, SaaS-abundance era, the tables have definitively turned.

Incumbents and intractable problems

Today, B2B problems and workflows are either already automated by an incumbent SaaS product or they fit into some remaining category that doesn’t have a SaaS solution yet. And why don’t they have a SaaS solution? Because they’ve been too freakin’ hard to build a successful SaaS product around. They generally fit into the following categories:

Too subjective or nebulous to automate with pre-AI SaaS (i.e. they require human judgement)

Too technically difficult or specialized to automate with SaaS (e.g. data is locked away in legacy systems that are highly custom to one specific company)

Too complex or high-level to automate with SaaS (i.e. large-scale processes across multiple teams and business systems that require complex coordination)

Too simple and cheap to bother automating with SaaS (e.g. saving a few people 10 minutes here and there)

These are the remnants of the SaaS revolution—the intractable problems.

So what does this mean for SaaS sales in 2025? You’re either selling against an incumbent or suggesting you can solve a heretofore intractable problem. In both cases, you’re going to have to take on more of the risk—it’s not 2015 anymore.

I think there are two main modes to doing this (whether used separately or in combination):

Own an outcome

Prove ROI first

Let’s dive into each.

Own an outcome

If your ROI case depends on a customer buying your software and reducing support headcount by 20%, then at some point after purchase the customer should actually reduce support headcount by 20%. They may be paying for your software, but they’re investing in an outcome.

Guess what? The days of sending them a login to your product and running a couple onboarding calls are over. To survive in 2025, you need to own an outcome.

Owning an outcome means doing whatever it takes to deliver that outcome for the customer. It doesn’t mean it has to be free, but it means you likely have to take responsibility for things that go beyond just access to software.

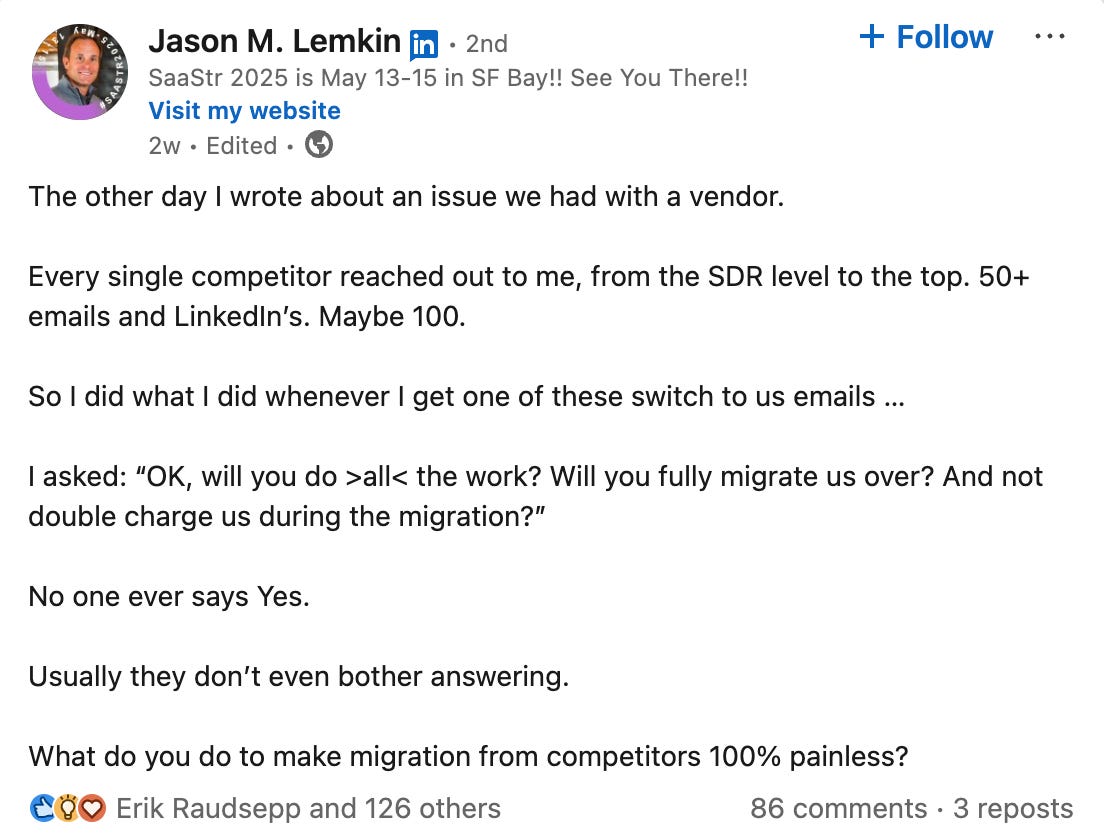

Whether it’s replacing an incumbent like Jason Lemkin describes above or a new approach to one of those intractable problems, owning an outcome probably means rolling up your sleeves and providing services around your product.

Unfortunately, this poses an economics problem.

SaaS companies have historically been valued on a healthy multiple of ARR4. This is because SaaS can operate predictably with high gross margins (75%+) making them (potential) EBITDA machines. They also have intellectual property that can scale. There’s a reason PE firms love to buy SaaS.

Services aren’t like that. They have much lower gross margins (30-50%), can be unpredictable, and have little differentiated IP—relying on hard-to-scale people. In short, services revenue doesn’t add much enterprise value.

SaaS companies would rather keep the “good” revenue and outsource services to others—think integration partners, consultants, etc. Or, even better, train the customer and outsource the work to them.

But, this dynamic fragments responsibility for the outcome. If the customer doesn’t get their outcome, is it because the software failed, the integration partner failed or the customer themselves failed?

From the customer’s perspective (the only one that really matters), the answer is you failed. You sold them an outcome they didn’t get. In 2025, that does’t mean they extend the contract and try again, it means they send you packing.

As a sales leader you need to think about how you could layer services into your offering so you’re not just selling software, but providing an outcome.

The industry is trending this way, driven by AI. Some vendors are already adopting outcome-based pricing and figuring out how to tie themselves directly to value.

There’s also good reason to believe that software vs services economics will change. As AI agents become more capable, they have the potential to deliver services with software-like margins: service-as-software.

If competitors figure out how to own an outcome by delivering a combination of product capabilities and AI-driven services while aligning pricing directly to value, it’s going to be very hard for you to explain to a prospect why they should choose your solution instead.

Prove ROI

It’s a time-honored tradition in SaaS sales cycles to provide The ROI Case. Your sales rep fills in a few cells in a spreadsheet Product Marketing built a few years and it spits out a 10x return. The rep copies this into their deck and proudly presents it on a call with the buying committee.

After that call, the CFO mentally marks every assumption down by 90% and asks the executive sponsor why think any of this might actually happen. If your rep’s done well, the sponsor may get through the interrogation by sharing your talking points. If the rep hasn’t, the whole thing falls apart then and there.

CFOs aren’t doing this to be mean.5 They’re thinking about the software they bought last year that isn’t fully implemented yet or the one that just didn’t work in their environment or the one that has half the internal adoption everyone expected.

Those products claimed they could solve some intractable problem or do things better than the incumbent. They all had rosy ROI cases. And now they’re all on locked-in contracts that represent underperforming investments.

Because of this, everyone has a much higher bar for commitment. ROI is now something you prove in the real world, not something you model in a spreadsheet. Until you do that, you’re not getting even a 12 month contract.

PLG does this naturally—a few people buy the product and show that it works. This increases confidence that it’ll work at a larger scale. On the other end of the spectrum proofs-of-concept (POCs) are pretty common for large enterprise software. These can often be large commitments themselves.

However, the middle-tier of SaaS doesn’t typically have a strong “prove it” motion. It’s another time-honored tradition for the prospect to ask for a POC and the sales rep to push back, saying it’s “not something we typically do”.

That needs to change. In 2025, if you’re not PLG, you need a POC.

You need to work with your team to make sure you can reasonably offer a POC. Like services, it doesn’t have to be free. But it does have to be a lower-commitment way of proving ROI before the customer commits fully.

This means training your reps on how to scope a POC, how to work with prospects to define success and how to drive the transition from POC to a longer-term contract. It also means working with stakeholders to figure out comp, make any necessary product changes, and align on who’s responsible for making sure POCs succeed.

Integrating POCs into you sales motion may feel like you’re just elongating the sales cycle, but a 90 day POC is way better than never getting the shot in the first place because the buyer just can’t take the risk on an annual contract without some real-world proof.

Wrapping up

The old B2B SaaS risk-sharing approach between vendor and customer is breaking down. There’s simply too much SaaS chasing too few problems—and the problems that remain are the hardest ones to solve.

Sales teams that win will assume more risk and still deliver. They’ll do what it takes to own a customer outcome from beginning to end and they’ll be willing to put some skin in the game with a POC that proves ROI before they ask for a long-term commitment.

If your team won’t do these things, someone else’s will. Better get to work.

I submitted this prompt to deep research and it generated this report. I spot checked the numbers and sources. They generally made sense so I think it’s a reasonable estimate.

Yes, we all had competition and churn but the demand was real.

PLG is a form of the risk-sharing I’m talking about. However, there’s usually a point where mature PLG companies ask their best customers to do larger rollouts and that transaction takes on many of the same dynamic I’m talking about here.

The rule of thumb used to be 10x. Now it’s more like 6x for public SaaS. This is wildly dependent on growth, market, buyer, etc.

Not most of them anyway.