The Power of Pipeline Coverage

A deep dive into a misunderstood metric.

tl;dr - Pipeline coverage tells you if there’s a chance to hit the number—when done right:

Calculate correctly: Compute basic coverage using a pipeline snapshot at the start of a period divided by the target. Snapshot pipeline throughout the period and divide by the gap to the target to get “to-go” coverage.

Do these: Regularly scrub the pipeline, determine optimal coverage based on historical pipeline conversion and use a consistent template to report weekly.

Don’t do these: Misalign periods (e.g. quarterly measurement for short sales cycles), assume pipeline coverage is the inverse of win rate or allow automation take away your “feel” for the data.

Read on for the full story.

It’s Pipeline Month here at Uncharted Territory. Today I’m focusing on a misunderstood metric: pipeline coverage.

Haven’t you heard? You’re supposed to have 3x pipeline coverage. The 3x “rule” is sort of a sales baba yaga—a boogeyman that young sales leaders are told about to keep them in line.

The somewhat fuzzy math behind the 3x rule breeds a specific kind of contrarian take that pushes back on pipeline coverage. Nate Nasralla has written thoughtfully about ditching the 3x pipeline coverage rule. Toni Hohlbein and Mikkel Plaehn went more clickbait with a podcast episode titled Pipeline Coverage is Worthless1.

This post isn’t about the the correctness of the 3x rule—I’ll tackle that later. Instead it’s about what pipeline coverage is for, how to measure it correctly and how to use it.

But first, I need to talk about Dave Kellogg and Kellblog. Dave’s written more intelligent words about pipeline on the internet than anyone else. If you write about pipeline metrics and don’t reference his work, you have to go to Posting Jail. I want to avoid that fate so prepare for some heavy citations.

Paul Stansik’s a close second to Dave with Hello Operator and his Sales Metrics Playbook. Paul’s been influenced by Dave, so really we’re dealing with the Dave Kellogg coaching tree of pipeline metrics here.

To some degree, I’m writing this for myself. We’ve struggled with the right way to look at our own pipeline coverage at Gradient Works. More on that later.

Let’s dive in.

What’s the point of pipeline coverage?

Sales leaders have one overarching job: hit the number. Per Dave Kellogg, you have to answer two questions to do this job well:

Are we giving ourselves the chance to hit the number?

Are we hitting the number?

Or, as metrics:

Do we start every quarter with sufficient pipeline coverage?

Do we have sufficient pipeline conversion to hit the number?

The purpose the pipeline coverage ratio is to tell you if you have a chance to hit your number. It’s that simple.

Now, Dave’s an enterprise guy, so he typically talks in quarters and 9-12 month sales cycles. Most readers of Uncharted Territory are more on the commercial side and tend to have shorter sales cycles. Before you dismiss pipeline coverage (like Toni and Mikkel), let’s replace “quarter” with a more general “period” (months would be more common in a commercial sales cycle).

The key here is that your measurement period must be less than or equal to your sales cycle length for pipeline coverage to be meaningful. You’ll see why in a moment when we talk about calculating pipeline coverage.

Calculating pipeline coverage (the right way)

Let’s start with the simple definition. At the start of each period (quarter, month, whatever), you take a snapshot of your pipeline with a close date in that period. Then, you take that number and divide by your target number for the period. Viola, pipeline coverage.

Let’s say at the start of Q1 your total pipeline with a Q1 close date is $3,250,000 and your target is $1,000,000. There you go, 3.25x pipeline coverage:

You can quickly see the problem with this if you calculate it for a period longer than your sales cycle. You introduce an unknown term: the pipeline that’s created-and-closed in period (call it C). That means your pipeline coverage is basically unknown.

Now you’ve either got to model C based on historical data or pretend it doesn’t exist and treat pipeline coverage as the inverse of your overall win rate (which it isn’t—more on that below). This leads to crazy numbers that pretend C doesn’t exist.

For example, a high velocity team with a 30-day sales cycle and a 20% win rate that tries to look at pipeline coverage on a quarterly basis would have to start every quarter at 5x coverage (based on inverse win rate). That has no basis in reality because they’re likely to create and close plenty of deals within that quarterly period. You’d have to radically overspend on demand generation to achieve this and that might blow up your CAC. This is the root of Toni and Mikkel’s hot take.

I know the pain personally because I’ve found myself doing it at Gradient Works. I’ve tried to run the business on monthly targets while looking at quarterly pipeline coverage—not great. This created a bunch of mismatches for incentives and measurement. The tl;dr is that we’re going all-in on quarterly because that aligns best with our own sales cycle.

This same cycle mismatch applies to anyone that’s looking at total annual pipeline coverage while running a quarterly plan. If an enterprise team with 9 month sales cycles is looking at 4 quarters pipeline coverage, they’ll be wildly wrong. They’ll have the create-and-close problem, but they’ll also have wildly optimistic pipeline numbers and close dates that are far in the future. I’ll bet the irrational optimism of far-future pipeline will outweigh the potential upside of in-period create-and-close every time and they’ll miss plan.

Isn’t pipeline coverage the inverse of win rate?

As usual, Dave Kellogg comes to the rescue here. He’s written a blog post and done an entire podcast on this topic. You should consume them both. Dave’s reasons are a little technical so I’ll summarize:

He defines win rate as a “period metric” that tells you what percentage of opportunities you won out of the opportunities that closed in a specific period.

He defines close rate as a “cohort metric” that defines what percentage of opportunities you ultimately win that were created in a specific period (i.e. their cohort).

He defines pipeline conversion rate as the rate at which you actually convert your pipeline coverage snapshot to revenue.

I could quibble with Dave’s terminology, but both the period and cohort metrics are valuable. I do agree that most people’s standard definition of win rate is the “period metric” he provides.

When you actually ask sales leaders about their win rates, however, they get sloppy. Most people give a range, but win rates are a point metric—you can’t actually have a range. What they’re really saying is that they vary a bit of over time (e.g. last quarter it was 22% and the quarter before it was 17%) or by segment (e.g. we close 20% in SMB and 15% in enterprise). They may even be mixing the period version (i.e. “win rate”) and the cohort version (i.e. “close rate”).

The thing that actually matters for pipeline coverage is the pipeline conversion rate. This will materially differ from win rate because your pipeline coverage snapshot will contain a blend of opportunities at different maturities. In most cases, mature deals will be overweighted in that pipeline and have a higher propensity to close. So pipeline conversion rate should, in theory, be higher than your overall win rate.2

Taking your pipeline coverage to go

So far we’ve defined pipeline coverage as a metric based on a snapshot at the beginning of the period. As the period progresses, deals get won or lost and pipeline values shift. Does that mean you need 3x coverage at all times? How do you track progress?

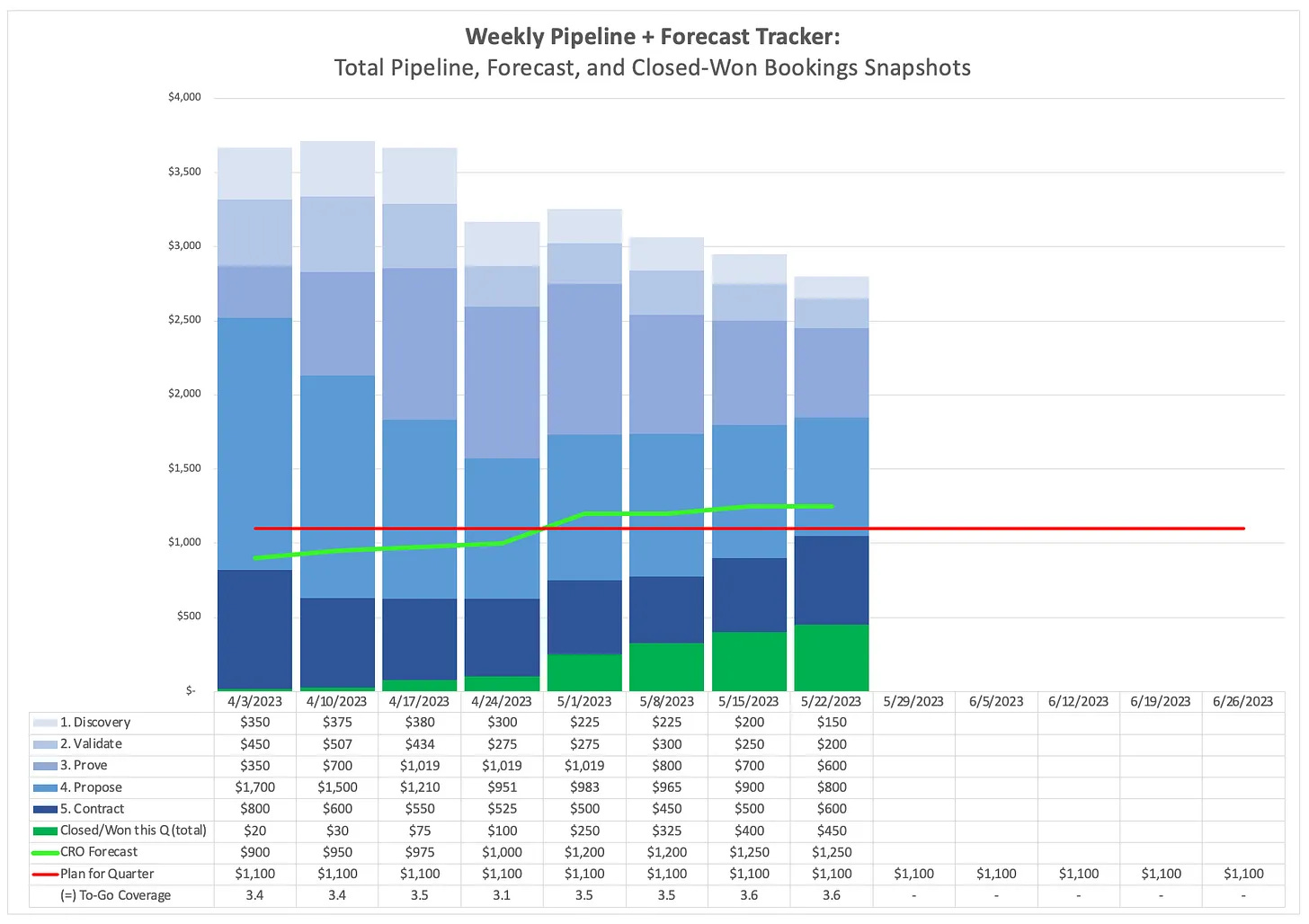

Let’s turn to Dave again and look at the idea of to-go pipeline coverage. It’s pretty simple: at all times your “to-go” level of pipeline coverage should be defined relative to how much you have left to sell in the period.

Basically, you should take your pipeline snapshot repeatedly during the period and compare it to how much you have to go to hit plan.

This is just a generalization of the start-of-period snapshot for pipeline coverage. At that point you (likely) have 100% of the plan to go. So it’s just a multiple of your overall target.

Paul Stansik from Parker Gale sums it up nicely in their Sales Metrics Playbook that describes how they do reporting with their portcos.

Again, Dave and Paul lean enterprise so they speak in quarterly plans and weekly snapshots. However, there’s nothing stopping you from using this same method on a monthly plan with daily snapshots.

Paul’s slide above highlights the need to always stay above 3x. There’s a little nuance there. In the early part of the period, to-go pipeline coverage should stay fairly stable, but over time it’ll likely start to decline a bit. It might even get close to 1 at the very end of the period since most of the remaining pipeline will either be closing in-period or get pushed to next period. That said, if you see it decline fast because you’re not converting pipeline into wins, you may have a significant problem.

What could possibly go wrong?

The major problem with pipeline coverage is that pipeline values and close dates need some basis in reality. Otherwise it’s garbage in, garbage out. Speaking of garbage, here’s a live look at pipeline data in most organizations:

Pipeline hygiene requires both inspection and scrubbing. Especially since reps really don’t like closing out pipeline—loss aversion is real even if it’s not particularly rational.

Pipeline inspection is a whole other set of posts. For now, I’ll focus on scrubbing. You’ll need to require your reps to to periodically scrub the pipeline to ensure you have good snapshots.

Dave takes this into account with his starting coverage snapshot, which he recommends you take at the beginning of week 3 on a quarterly plan or day 3 on a monthly plan. The idea is that you want to give the reps a little time to fix close dates and pipeline values before you take your first snapshot.

I think of this first snapshot as the “official” snapshot because it’s the one you can use as the basis of your historical pipeline conversion rate. That number will ultimately guide the pipeline coverage ratio you need to start each period.

You might think that operating on a to-go basis with weekly/daily snapshots removes the need for this kind of scrubbing—and it does to a degree. It’s still important to reinforce to the reps that there are points in time where the pipeline must be as clean as possible. As Dave says, if you’re always scrubbing, you’re never scrubbing.

Operationalizing pipeline coverage

You don’t need to start from scratch. Go download the Sales Metrics Playbook. It’s got a ready-made reporting template you can start using. Here’s a screenshot:

You may be tempted to automate this, especially if you’re operating on a monthly plan. You should work with your ops team to get a pipeline snapshotting strategy in place but beware too much automation.3 When I talked to Paul about this, he extolled the virtues of keying this information into a spreadsheet manually to maintain “finger-tip feel” for the data. I can’t say I disagree with that.

Wrapping up

It’s easy to see how pipeline coverage gets a bad name—misapplied periods, bad pipeline data and the 3x mythology all contribute. However, there’s a reason very smart people like Dave Kellogg focus on it so much. It’s the key to answering the first of the two key sales questions:

Are we giving ourselves the chance to hit the number?

Are we hitting the number?

If you can’t answer #1, you might as well assume the answer to #2 is no. And if #2 is no too often, you’ll need a new job.

The episode is somewhat more thoughtful than the title. It should probably be titled “Pipeline Coverage as usually understood is not very useful for tracking progress in a high velocity sales motion where there are lots of opportunities created and closed in period.” But that doesn’t roll of the tongue.

This provides a clue as to why 3x actually works ok as a rule of thumb.

This is actually a harder than it sounds since CRMs suck at tracking historical data in a useful way. If you’re on Salesforce, a good place to start is with Reporting Snapshots.