Tariffs, Trade Wars and SaaS Explained

Making sense of a wild week in trade for SaaS sales leaders.

On Monday I gave my team my own version of the RIP Good Times talk. Except the good times weren’t all that good, because we’re on the 3rd major crisis of the last 5 years. COVID hit in March of 2020, SVB collapsed in March of 20231 and last week the market began hemorrhaging to celebrate the “Liberation Day” tariffs announced on April 2nd.

I wrote the above paragraph at about 5:30am CT Wednesday morning. As I write this at 2:30pm CT, we now have a 90-day pause on some of the tariffs. The market is way up but still well below its most recent highs. I won’t get any more specific than that because who knows what’ll happen between now and when you read this… or over the next 90 days, for that matter.

And that’s the issue.

The environment for doing business across borders is different today than it was two weeks ago. Regardless of what actually gets implemented, the uncertainty will remain—combined with long-term damage to America’s reputation as a reliable trading partner and the world’s preeminent place to do business. This is true regardless of whether you support tariffs as a policy or not (and I do not).

So, tariffs are here and they’re going to have an impact. As leaders we have to decide what to do about them. The problem is most of the tariff discourse comes in two flavors: fact-free political invective or wonky macroeconomic analysis. I thought I’d use this newsletter to try to look at what all this might mean for SaaS sales leaders.

I’ll do my best. While I’m reasonably well-read on the subject and willing to do some research, I’m not an economist. I do at least know a thing or two about 20th century US history—the focus of my history minor lo all those years ago. That means I knew about Smoot-Hawley before it was cool. That’s gotta count for something, right?

The tl;dr

Tariffs are a tax on physical goods crossing a border at a port of entry. They don’t directly impact software. However, they will impact your business in two ways2:

While the US typically runs a trade deficit with most countries in goods, it usually runs a surplus in services. In a full-on trade war, countries will find a way to hit us where it hurts—perhaps in the form of increased digital services taxes (DSTs).

Tariffs make nearly every physical good more expensive because nearly everything we buy is the end result of a complex international supply chain. While your software may be exempt, your customers or prospects who buy or sell things involving atoms will feel the heat. They may be more interested in preserving their actual business than buying your software.

With that tl;dr out of the way, let’s do a quick tariff 101. After that we’ll look at the potential for DSTs to be weaponized as retaliation in a trade war and then wrap up with a few notes on customer impact.

What are tariffs, actually?

As I started my research, I realized I didn’t have a great handle on tariff mechanics. Maybe you feel the same so we might as well cover the basics.

Tariffs are a tax paid by the company importing a product3. In the US, the importer ultimately pays Customs and Border Protection fees based on the declared value of the goods being imported. This money goes to the US treasury. Let me just say that again: the importing (US) company pays, not the exporting (foreign) company.

The Wall Street Journal has a great explainer with a handy diagram:

Tariffs make imported products more expensive. Importers may eat some of the tariff cost in the form of lower margins, but they will have to pass along some of it to buyers in the form of higher prices. The primary rationale for tariffs is that this will “protect” domestically produced goods by making them more appealing vs imported substitutes. That said, it may be literally impossible to make some products domestically. That would raise the price of those goods to approximately infinity.

Complex supply chains blur the line between domestic and imported. So yes imported products get more expensive. However, the last 80 or so years of free trade mean that you can rarely just substitute a fully “made in America” product for an imported one—many products are essentially both. This means the cost of pretty much every physical good will need to increase to compensate.

Tariffs increase the chance of a trade war. Naturally countries that export a lot of goods to the US will feel attacked and want to do something about it. They’ll charge a tariff on US goods entering their countries, paid by their importers, raising prices on US exports and reducing demand for those exports. Of course, reciprocal tariffs are just one of many ways to retaliate in a trade war.

Tariffs apply to physical goods, not digital services like software. The US runs a trade deficit in physical goods with many countries but a trade surplus in services. Digital services do have some barriers in the form of digital service taxes (DST). And those might be something to worry about for software businesses.

Tariffs and digital services (like yours)

The blanket “liberation day” tariffs appear to be based on each country’s trade surplus with the United States using a very naive formula.

That doesn’t make a ton of sense. If you sell widgets and someone buys a widget from you for $100, you’d have a $100 “trade surplus” (you got $100 and gave them a widget) and they would have a $100 “trade deficit” (they got a widget and gave you $100). It’d be a little weird for them to get super mad at you about that.

Why’d I use “widget” in the last paragraph instead of “software”? Well, economists break up international trade balances into two categories: goods and services.

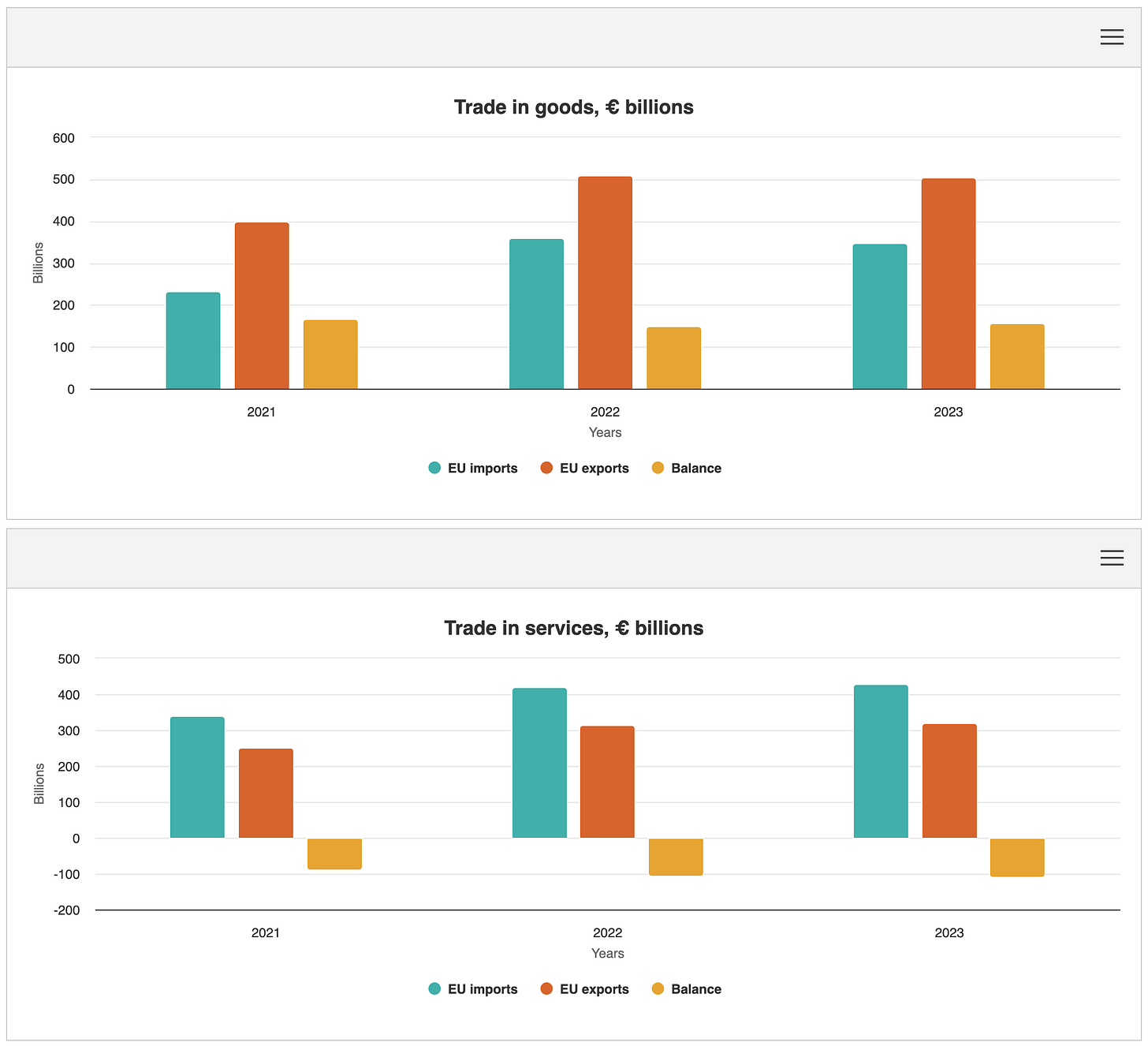

The US tends to buy more physical stuff from other countries than it sells to other countries.4 We run a deficit in goods. At the same time, we sell more services (software, consulting, etc) than we buy. We run a surplus in services.

Here’s what that looks like between the EU and the US (from the EU’s perspective):

The EU has a trade surplus in goods and a deficit in services with the US. Therefore, the US has a trade deficit in goods and a surplus in services with the EU. If other countries were to adopt the same logic as the US tariffs—surplus good, deficit bad—they’d want to make our services more expensive so domestic options look better5.

The problem is that services don’t have a port of entry and can’t really be subjected to tariffs. That’s where digital service taxes (DSTs) come in. Here’s how the international law firm Skadden describes DSTs:

DSTs are taxes levied on revenues generated from certain digital services, such as online advertising, digital intermediary activities and the sale of user data. Countries implement DSTs to collect revenues from multinational companies providing digital services in their jurisdiction even if these companies do not generate income through the ownership of assets there.

Europe has quite a few of these taxes already. The USMCA, which replaced NAFTA in Trump’s first term, requires equal treatment of services but Canada went ahead and enacted a DST anyway. The point is these mechanisms for applying tariff-like taxes to services already exist.

Today, most DSTs seem targeted at data, advertising and streaming—not SaaS—but that could change. Earlier this week, in response to the new tariffs, France suggested they could go after digital services including ones “that are currently not taxed”.

If we really do end up in an all-out trade war, you might find yourself paying taxes to sell SaaS to other countries.

The impact on your customers

I’m going to leave the in-depth analysis of this to the economists and the gamblers. However, it’s fair to say that we’re now dealing with uncertainty. IPOs have been delayed and Wednesday morning we started to see early signs of a 2008-style financial crisis brewing. Luckily, that acute turmoil eased up with the 90-day delay.

All this happened before the tariffs actually had a chance to really take effect. And let’s remember we’re not out of the woods yet. As of this writing there’s still a 125% tariff on Chinese goods, historically high tariffs on Mexico and Canada, as well as a 10% blanket tariff. There’s still a lot that’s going to happen here.

It’s fair to imagine that CFOs and investors are going to hunker down to see how this plays out. There’s a good chance hiring plans will be delayed and purchases get even more scrutiny. 2024 loosened things up a little but I’d expect the rest of 2025 to look more like 2023.

Plan for more pipeline coverage to guard against forecast uncertainty. Make sure your ROI cases are absolutely air tight. RIP good times. You never even really got started.

A brief historical coda

In the 1800s the US had very high tariffs, but we also didn’t have an income tax. Tariffs were one of the few levers the government had to raise revenue.

Smoot-Hawley went into effect in 1930 as a way of trying to protect US businesses during the great depression. It didn’t.

As you can see from the chart above, the April 2nd tariffs would bring us back up to a level higher than even the highest point during Smoot-Hawley.

In between was a period of relatively stable tariffs and carefully managed trade relationships. This was part of the post-World War II Pax Americana where the United States led the world towards a rules-based order. That order has helped make our lifetimes more peaceful, more humane, more wealthy and more free6. That’s not altruism—it’s enabled us to create an economy that’s the envy of the world and the greatest engine of innovation in history. We break that at our peril.

But that’s enough of that. This is a CRO newsletter, not a Wendy’s.

SVB was more of a single crisis moment in the long-rolling reckoning for VC-backed software starting with the end of ZIRP. One might call it a particularly cold and stormy day in the SaaS winter.

Possibly 3, but if the cost of cloud infrastructure increases because chips get caught in the trade war then we’re all going to take a nasty COGS hit.

This is not a political statement. A tariff levied by the US is paid to the US government by the company importing the product.

This is why a lot of developing countries have super high tariffs under this formula. They make stuff we buy (like Nikes) but aren’t yet rich enough to buy the stuff we produce (like aircraft).

If you think it sounds ludicrous for Europe to make their own version of every US software company, consider applying that same logic to manufacturing every part of every consumer product right here in the US.

Not for everyone and not always. Fully living up to our lofty ideals has always remained out of reach.