Traditional Territories Hurt Commercial Sales Teams

The dynamic books approach is a more efficient alternative.

tl;dr - Static geographic territories are a bad fit for commercial sales teams—dynamic books maximize account coverage, pipeline and revenue.

Traditional territories are outdated – Sales teams have carved geographic territories for a century. This approach is rigid, inefficient, and leaves revenue on the table.

Territory planning is a nightmare – Annual re-carves are a low-information, high-stakes process that takes months, yet still fails to create fairness or balance.

Dynamic books are better for commercial sales – Instead of fixed territories, give reps an evolving book of accounts based on quality, buying signals and rep capacity. This boosts pipeline by ensuring reps work the best available accounts.

Read on for the full story.

Sales has changed a lot in the last century. Our approach to sales territories hasn’t.

According to George Frederick, author of 1919’s equivalent of Predictable Revenue (Modern Salesmanagement), the best—and only—territory designs were based on geography. Poor railroad service, limited trucking capability, and a lack of mass media limited a company’s sales radius. Territory was completely synonymous with geography1.

Even in 1919, Frederick thought some elements of geographic territories were already outdated:

Fast forward 106 years to last week. CJ Gustafson (who writes the excellent Mostly Metrics newsletter) published Your Complete Guide to Sales Territory Planning. It’s very thorough and also very thoroughly geography-based. I’m willing to hazard a guess that George Frederick would find the content familiar (after getting over his shock at the strange thinking machine showing him said content).

I’m going to argue for an altogether different approach. It’s not for everyone. But if you run a commercial inside sales team that’s trying to cover a sizable TAM, it’s very much for you. It’s called dynamic books.

But first, let’s examine the status quo.

The trouble with (static) territories

Territories are one of the biggest sources of strife in sales. Just ask any rep why they left their last job. You’ll hear one of 3 reasons: their manager, their comp or their territory—and those last two are basically the same thing.

Traditional geographic territory models fail to account for the complexity of modern sales and leave unrealized revenue on the table. They’re inflexible, often outright unfair, and no matter how much time a team spends on annual territory planning, they're never perfect. In fact, they’re rarely even very good.

That’s because opportunity is not distributed geographically and we’ve built an incredibly complex set of practices to design around that fact. These practices are so common that they’re accepted without question—grass is green, the sky is blue and territories are patches carved up once a year.

Let’s try to look at the process with fresh eyes.

Territory design is hell. It’s months of data cleaning, spreadsheets and horse trading. (I should know. I once lived through a 9-month territory process that ended in a stalemate.) Just say the word “holdover” to a RevOps person in December and see them cringe. And don’t get me started on geographic questions about buying centers and HQs in a world where buying committees consists of 12 people in 6 states and 3 countries.

Because it’s so hard, we can only afford to do it once a year. This means it’s inherently low information and high stakes. It’s very difficult to predict with certainty that a territory carved in November will yield what a rep needs in July. And once the territories are carved, it’s incredibly disruptive to change them.

What do we do to mitigate all this risk? Aside from a lot of performative CYA analytics, we pad territories with extra accounts, creating unworkably large territories which are impossible for reps to effectively prioritize.

After rolling out territories, the work isn’t over. Ongoing territory management is nearly as challenging. How do you keep territories balanced as accounts get disqualified? How do you handle unequal inbound flows? How do you deal with rep complaints and rules of engagement conflict? How do you handle rep attrition and the dreaded empty territory? How do you ensure you’re covering your TAM?

Given all this it’s no surprise that 64% of teams report they’re not satisfied with their territory design. Why should they be? The status quo sucks.

Reps suffer. No matter where you look, stats on rep attainment are dismal. In the 2024 SaaS Metrics report from The Bridge Group, they report 51% of reps hitting quota. Other sources put that number as low as 31%. It’s not pretty.

The entire team suffers. Poor territory design can lower revenue outcomes by as much as 10%2. Who wouldn’t want 10% more revenue from the same reps?

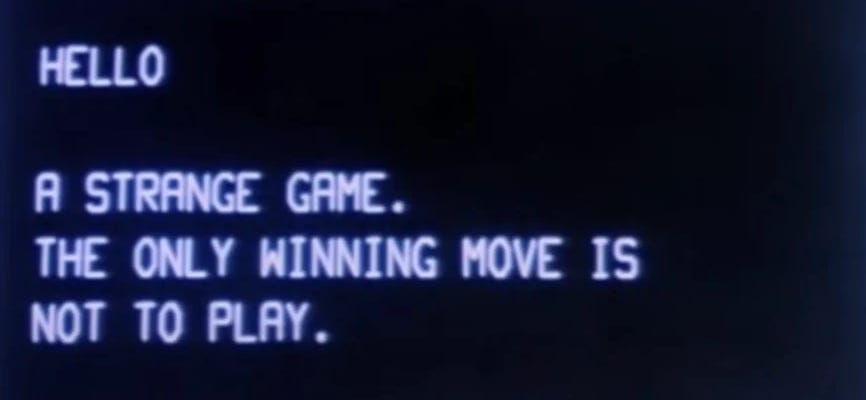

And yet, we’ve played the game this way for 100+ years. Perhaps we shouldn’t.

Introducing dynamic books

Think of dynamic books as high-velocity named accounts. The most aggressive form of dynamic books gets rid of geography entirely and gives reps an evolving book of accounts.

Where static territories treat a list of accounts (the territory) as fixed and a rep as changeable (e.g. a rep is assigned to a territory), dynamic books approaches the problem differently.

Dynamic books assumes both the set of reps and their list of accounts (their book) can change over time. This more closely resembles the reality of a sales team and their market than the static model.

This model reflects a set of interlocking best practices derived from the trenches—including my lived experience across multiple high-velocity sales teams. I’ve also been lucky enough to help more than 25 different companies implement this model. Even if you’ve never called it “dynamic books”, many parts of this will look familiar to folks that have worked in commercial sales. In fact, this approach to account coverage is one of the pipeline secrets of Vertical SaaS.

Let’s dig in.

The dynamic books model in detail

Instead of attempting to carve up the world once a year into semi-equal revenue potential patches, we start by considering how many accounts reps can actually work at any given time.

This is a bottoms up process that considers what it takes to actually work an account. The basic idea involves considering how many touches (activities) you consider necessary for an account to be “worked” vs how many activities a rep can actually do in a day. In many cases, these numbers work out to a load of ~100 accounts for a mid-market rep with more for an SMB rep and fewer for enterprise.

Armed with the knowledge of rep capacity, we take all our eligible accounts—irrespective of geography—and rank them based the information we have at the time. This includes firmographics, technographics and any kind of intent/signals data. This ranked group of accounts is called the ready pool.

Next we take the top set of accounts and assign them out to reps to work. We call this a distribution. For example, if we have 10 reps who can each work 100 accounts, we take the best 1,000 accounts and assign them out across those reps. The remaining accounts stay in the ready pool and are nurtured by marketing.

Once reps start working their accounts they’ll do one of two things: turn the account into a customer or learn something about the account that makes them unable to proceed. At that point they return the account for rest & review. If there’s something in particular wrong with the account, it may be permanently disqualified.

If you think about it, this disposition process happens with static territories as well—just without any real structure. Reps learn something disqualifying about an account and tuck it away somewhere with a note (if you’re lucky) in CRM. It lingers in their patch as a distraction and the knowledge gained through outreach isn’t captured in a usable way.

After a little while, reps who were previously at max capacity now have available capacity. You then top them off with the next best set of accounts from the ready pool and the process continues. This happens frequently; many Gradient Works customers run distributions weekly or even daily. In this way, you’re always working the best possible accounts for a given amount of quota capacity.

There are two other aspects to the model:

Retrievals (aka use it or lose it) - Each rep has a set of the best possible accounts the company has to offer. If they’re not working them, those unworked accounts can be redistributed to another rep with capacity. This is a powerful stick that drives account coverage.

Inbounds and signals - When there’s a hand-raise or an intent signal on an account in the ready pool, that account is assigned to a rep with the capacity to take it on. Think of this as a capacity-aware round robin process. For an account that is currently owned by a rep, they get a notification of the signal.

How to get 33% more pipeline (an example)

Jane has the Midwest territory with 600 accounts, and Joe has Northern California with 400 accounts. During territory planning, we did our best to establish that these have equal revenue potential.

However, revenue potential is a one-time estimate—it’s highly unlikely these accounts are truly equal. And, of course, they won’t all be in-market at the same time. Jane’s territory may only have 50 in-market high-quality accounts, while 150 of Joe’s are great.

Further, let’s say that each rep can really only work 100 accounts at once3. Jane will use her time finding increasingly creative ways to reach out to her 50 good accounts or drum up business on the 550 remaining marginal accounts, while Joe focuses on the top 100 best accounts and ignores 50 good ones (as well as 350 bad ones). That’s the static territory model—one rep starves while another is leaving potential revenue on the table.

With dynamic books, Jane and Joe would split the 200 high-quality accounts evenly and each work 100 accounts. Both reps would be equally fed, and have equal opportunity to hit quota.

Let’s assume a conversion rate of 10% on high-quality accounts for this example. Given that conversion rate, here are the metrics:

Static Territories

Jane: 5 opps (50 x 10%)

Joe: 10 opps (100 x 10%)

Total: 15 opps

Dynamic Books

Jane: 10 opps (100 x 10%)

Joe: 10 opps (100 x 10%)

Total: 20 opps

That’s a 33% increase in pipeline with the same accounts and same quota capacity.

What about the lower-quality accounts? They go into a general account pool. They’re nurtured by marketing and assigned later if a) they demonstrate buying signals or b) there’s no more valuable accounts to work.

How it works in the real world

You don’t have to have Gradient Works to implement dynamic books and I’m not here to sell you on our pipeline platform (though you can certainly talk to us if you want). However, we help companies adopt dynamic books all the time and these benefits aren’t just theoretical. A mid-sized data and services provider for the CPG industry adopted dynamic books and saw their win rates increase from 13% to 20%. Companies like Box have adopted this model for their commercial team and seen ACVs increase.

Dynamic books isn’t for everyone

Some teams shouldn’t use dynamic books. Enterprise teams should work small sets of named accounts over a long period. Insurance companies have a very good reason to organize by geography because each state has different laws.

We’ve found that dynamic books works best for commercial sales teams that operate at a higher velocity. To understand why, let’s consider where dynamic books sits in the overall taxonomy of territory designs and why you might choose a specific design.

Static Models (one-time “carves”)

Geographic - You have field sales, extensive market data and highly predictable sales patterns OR there’s a material variation in sales process across geographies.

Vertical - Your GTM requires high specialization for different verticals and you have enough market data to be confident about demand in those specific verticals.

Named Accounts - You have a long sales cycle that requires building relationships and value over time along with high confidence in specific accounts that you want to target.

Dynamic Models (continuous allocation)

Round Robin - Your GTM is mostly inbound-driven, sales cycles are relatively short, you have a small sales team and those reps have mostly the same length of tenure.

Dynamic Books - You have relatively fast sales cycles, have a hybrid inbound/outbound model, and are dealing with demand and headcount uncertainty OR you’re trying to maximize coverage of a large TAM.

Assuming you fit the dynamic books mold, you probably have questions. Luckily I’ve got answers based on real world experience.

Dynamic books FAQ

When I introduce dynamic books to an audience, I get lots of questions. Here are answers to the questions I get most frequently.

Won’t my reps feel a lack of ownership?

The idea behind static territory models is that the reps “own” a patch. There’s the old sales saying: “you’re the CEO of your territory.” The reality is most territories contain large numbers of unworked accounts. With dynamic books, reps are entirely responsible for continuously engaging a smaller set of accounts. Further, they can’t disposition an account (and free up capacity) without checking off ROE boxes. That drives new levels of ownership and accountability.

Am I just going to take accounts away from reps?

This model gives reps a significant amount of control. So long as they’re working them, accounts stay in their name. Retrievals only happen if a rep has chosen not to do the work—essentially voting that an account isn’t worth their time. Crucially, this model also doesn’t assume an annual shakeup where accounts get moved around willy nilly at the beginning of the year due to a re-carve.

What about relationships?

If reps believe they’re developing a meaningful relationship, they’ll work the account and they’ll keep the account. They vote on the relationships that matter with their actual work, not talk about supposed rapport with some POC.

What about vertical specialization?

I’m guilty of believing that vertical specialization is overrated in many cases. If, however, you do have a truly different sales motion or offering by vertical you can set up separate dynamic books processes within each vertical. This is only relevant, of course, if you have multiple reps focused on each vertical. If you’ve made the (risky) decision to have one rep per vertical, then there’s very little to be gained from using dynamic books.

What about global theaters and time zones?

It’s usually not great to have a US rep working an APAC account—the time difference is just too much. It’s less bad but still sometimes problematic to give a West Coast rep an East Coast account. It’s perfectly reasonable to segment your dynamic books process by theater (NA, EMEA, APAC). We’ve also seen several successful dynamic books implementations that have separate pools for US East and US West. I don’t, however, recommend getting more granular than that. Once you get into Northeast, Southeast, etc you’re basically reinventing geographic territories and losing many of the efficiency benefits of dynamic books.

This requires great data and my data’s not… great.

Well, first of all, this isn’t really a question, but I get it. Nobody has good data. The problem is you still have to execute. I’d actually argue that static carves are riskier in the face of bad data. Since a pre-calculated revenue potential is so important to the process and after-the-fact change is so hard, a static carve with sub-par data is super risky. What usually happens is that the bad (or missing) data problems get outsourced to reps to resolve. What I like about the dynamic books model is that it lowers the risk of an individual data mistake and creates a resilient “self-cleaning” process. If a rep encounters a poor account in their book, they can return it, RevOps can review it and either fix the problem or disqualify the account. In a static territory, these kinds of data problems often stay hidden.

How does this work with AE-SDR pods?

Short answer: just fine. However, pods in general have some issues. My personal preference is that the SDRs have a pool of accounts they own and work separate from any individual AE. Once they set a meeting, they pass along the account to an available AE. AEs would also have their own books and outbound targets. In this “pool” approach, dynamic books process would assign some accounts to SDRs and some to AEs. You can certainly create pods and still use dynamic books—many Gradient Works customers do. In that case, the SDR books are mapped to the books of the AEs they support. As those books change, the SDR books do too.

Wrapping up

For a century, we’ve largely approached territory the same way—carving up patches once a year, handing them to reps and hoping for the best. It’s such an ingrained process that many sales teams never question it. It’s just “how it’s done” even though the status quo is unloved, painful and fraught with risk.

Dynamic books isn’t for everyone. However, for commercial sales teams searching for extra pipeline and extra efficiency it’s a battle-tested way to approach an age old problem.4

I mean it’s called a territory for a reason.

A team from ZS Associates found that better territory design could yield a 2-7 percentage point increase in revenue from the same resources. The Sales Management Association found that better technology approaches to territory design yielded a 10% higher achievement of objectives.

For more on this, see Why More Prospects ≠ More Pipeline.

I ran out of space in this article, but if you want more detailed advice on how to actually implement and manage dynamic books, there’s a lot more information on the Gradient Works Dynamic Books Hub.