Taking the Terror out of Territories

It won't be a dream, but it doesn't have to be a nightmare.

It’s October and Halloween’s only a few weeks away. It’s a great time of year because it gives me an excuse to do something I love: watch horror movies. I’ve watched a lot over the years, so I don’t scare easily—at least when it comes to movies.

One thing that does scare me? Carving territories. It’s time-consuming. It’s frustrating. It’s high-stakes. Do it wrong and, not only will you miss the number, you’ll start losing disgruntled reps along the way.

I’m not alone in this. I’ve been talking to a lot of RevOps teams lately about how they’re tackling territories and I’ve heard the same language again and again: “pain”, “nightmare”, “awful”. Sounds appropriate for the Halloween season to me.

Below I’ll dig into why there’s so much angst and how to make it a little less horrible for everyone on the GTM team. But first, a quick digression to what we talk about when we talk about territory.

Territories aren’t (just) geography

Most sales teams default to the assumption that there’s one way to do territories: carve up the world into little geographic chunks once a year, hand a chunk to each rep, and say “go get ‘em tiger”.

I firmly believe this traditional approach to territories leaves much to be desired.

For higher-velocity inside sales (like most B2B SaaS) it makes no sense to carve up the world once a year. Dynamic books is the answer. Just skip the one-time, high-stakes carve and allocate accounts on demand, based on capacity, in real time1.

Dynamic books isn’t always the best fit, though. It works best for commercial sales orgs where there’s a large pool of similar accounts. In keeping with the theme of this newsletter, it’s a bit more like managing a herd of cattle.

But that’s certainly not every sales process. Sometimes relationships and/or specialization are dominant factors. You’re no longer dealing with a herd, you’re dealing with unique individuals that have specific needs, requirements and potential. That calls for a more traditional approach.

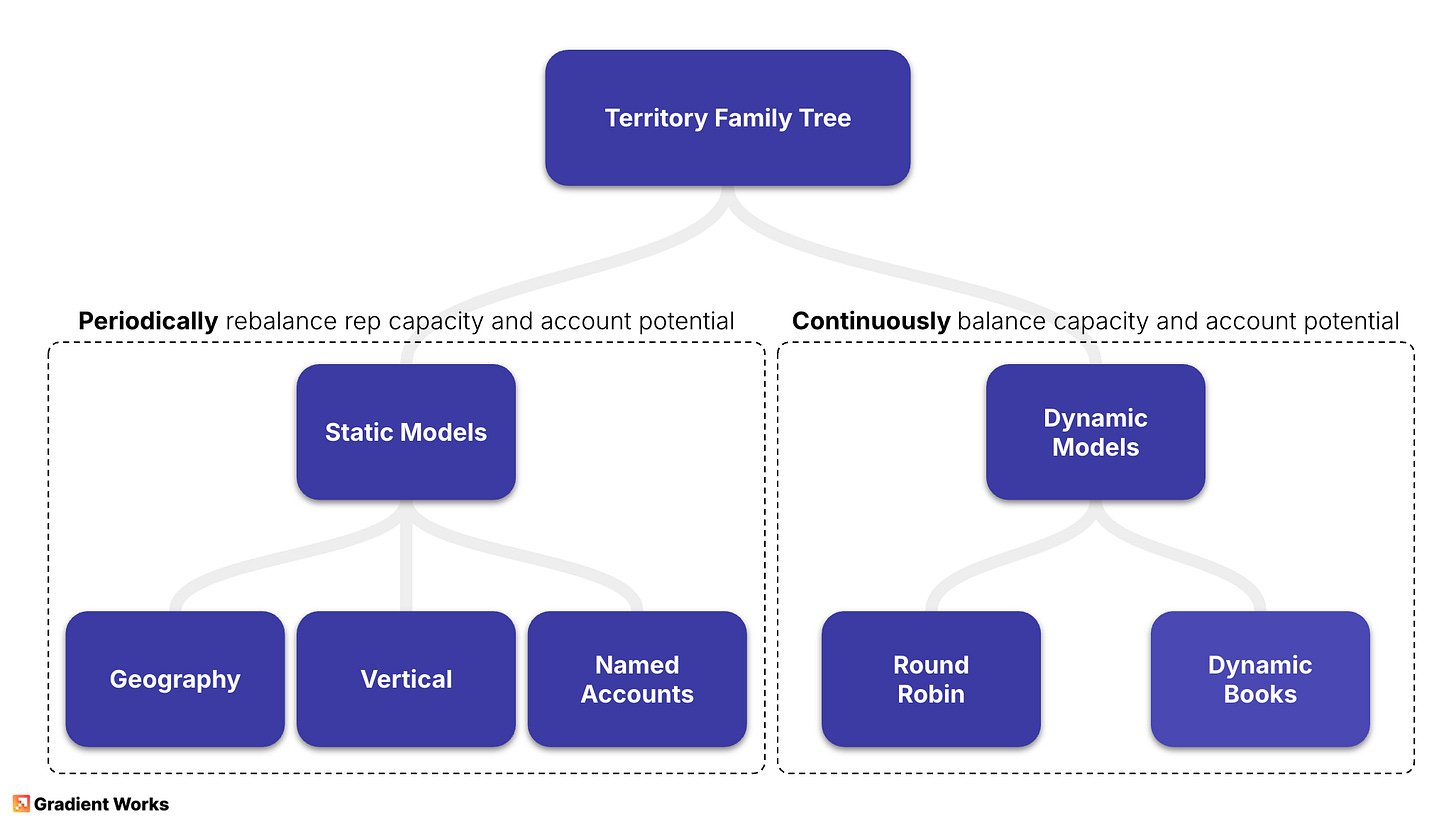

I made this handy chart to help choose a territory approach:

Here are some reasons you may find yourself gravitating to the left half of this chart:

Complex sales - strategic and enterprise sales need expertise and deep relationships. These books require careful thought and balancing, usually ending up in a named accounts model.

Customers - you owe it to your customers (especially the larger ones) to maintain consistent personal relationships where possible.

Skill specialization - while I personally think many companies over-index on vertical knowledge, sometimes there really are large enough differences that rise to the level of a primary driver of territory design. For example, selling insurance requires specific credentials that are issued on a state-by-state basis.

Localization - some businesses really are local, either because they operate in hyper-specific physical markets (e.g. construction) or they have local requirements (e.g. languages in EMEA).

Most of the rest of this article assumes you’re in one of the categories above and find yourself gravitating towards the need to “carve” static territories.

You can’t spell territory without terror

Planning season isn’t fun for anyone, but it’s especially hellish for the people responsible for building the territory model—usually RevOps. It’s weeks of data cleaning, spreadsheet manipulation and horse trading. (I once lived through a 9-month territory process that ended in a stalemate, iykyk.)

We’ve established that RevOps folks viscerally hate territory planning. I’d like to contribute to the cause of GTM team harmony by looking at why this particular process provokes such a strong reaction. And then, possibly, what could help.

First, building territories is seriously—and provably—complex.

One of the things you learn as a Computer Science undergrad is something called the knapsack problem. Let’s say you’ve got a bunch of items, each with a certain size and value. Your job is to fit a set of them into a fixed-size sack while maximizing the total value of all the items. Remind you of anything? Like, say, maximizing revenue potential in a territory without giving someone so many accounts they drown?

The reason we learn about this problem is that it’s one of a special group of very hard problems that touch on a (very technical) mystery at the heart of computer science—one that’s eluded the smartest people in the world for the last 50+ years. So, that might be one reason your RevOps leader seems a little frazzled come territory time.

Second, territory designs are filled with dependencies2 which means there’s a very strong butterfly effect. Let’s look at a real definition of butterfly effect (not the 2004 movie starring noted tech investor and ‘70s himbo Ashton Kutcher):

In chaos theory, the butterfly effect is the sensitive dependence on initial conditions in which a small change in one state of a deterministic nonlinear system can result in large differences in a later state.

In short, updating some data, tweaking a balancing rule or adding a few holdovers means a) you often have to rebuild the whole territory model from scratch and b) the resulting territories might look very different.

The final reason for all the pain has nothing to do with math and everything to do with people. Territories deeply impact the whole GTM team which makes the number of stakeholders enormous. Everyone from the CEO to the most junior SDR has a stake in the success of any given territory plan. A quantitatively “perfect” design means nothing if enough reps feel like it’s too disruptive or unfair. This is what makes territories more art than science.

Ok, so this is a pretty miserable problem. Thankfully, there are a few things we can do to make it a little less bad.

How to make territories less terrible

Here are three things you can do to make the process more tolerable:

Make time for data improvements

Set the strategy first

Reduce the exceptions

Let’s look at each in turn.

Dealing with data

Let’s get this out of the way: there is no such thing as “good data”, only less-bad data.

The first thing that makes territory design easier is investing in your data up front. Make sure the RevOps team has the time and budget required to enrich accounts with ICP-related data. Try your hardest to get broad agreement on the data that will be necessary for the process. Casually tossing in other data points later in the process can easily trigger the butterfly effect I mentioned up above.

Pay special attention to hierarchy data in particular. Many (most?) territory carves hinge on hierarchies, requiring territories to be built around account families and not individual accounts. One sure way to frustrate your reps is to assign HQ to one person and some set of subsidiaries to another.

Just remember, your data will never be perfect and you could spend infinite time and money trying to achieve the impossible. It’s important to timebox this enrichment phase to a relatively short period at the beginning of the territory design process.

Start with strategy

Looking at the territory taxonomy from above, there’s a key underlying idea. The choice of territory design should reflect a choice of GTM strategy—one built on a clear ICP and segmentation.

In short, the strategy definition should come before the territory design. But that’s not always the case.

It’s no surprise why this happens. These strategic choices aren’t easy. The data (even after investing in enrichment) is usually ambiguous3 while the opportunity costs of locking in a path are significant. Very few companies can allocate all the resources they want to every potentially relevant market segment. Say you decide to focus on the enterprise. That means giving up on smaller deals that might move faster. Where do you draw the line on what counts as “too small”?

You have to actually make these hard choices. A poorly defined strategy leads to poorly defined priorities. Poorly defined priorities lead to poorly designed territories.

Think about it: you want white glove service for your existing customers because you believe service is a competitive advantage AND your board wants attachment revenue from new AI Product X. You balance your territories on equivalent expansion potential but also try to cap them on total customer count to provide good service. Which takes precedence when those goals conflict? That’s a strategic decision, not something for RevOps to “just figure out”.

Too frequently, territories and strategy evolve simultaneously during the planning process. Some of this is inevitable, but it has a real cost. Each time the strategy changes, you’re back to re-packing your knapsack and experiencing the butterfly effect.

Exceptions should not be the rule

We all expect territories to have some subjectivity. Most of us want reps to have some say in how their territories are constructed and we want to let our managers exercise some discretion. After all, these are the people who are “on the ground” with prospects and customers. They should have the most context.

It’s easy, however, to take this too far. Allowing reps to designate a few holdover accounts is fine. Allow too many holdovers and reps effectively hold veto power over the strategic balance you’re trying to achieve with your territories.

The same goes for manager discretion. A few tweaks here and there based on some insider knowledge is fine—wholesales overrides of rules-based assignments are less so. Not only can this easily throw off territory balance, it introduces the potential for perceived (or real) bias.

The best territory designs are rules-based, transparent and provably balanced. Use exceptions sparingly.

Wrapping up

Designing territories, like annual planning in general, isn’t going to be a lot of fun. Not only does this process contain a complex optimization problem, it’s also very easy to get deeply entangled in stakeholder politics. Like much of sales, it’s a tricky combination of math and people.

That said, it doesn’t have to be quite so hellish. If your team can invest in the data, answer the tough strategic questions first, and limit subjectivity you’ll have a good shot at taking the terror out of territories.

Additional Reading

Here are a few related articles that you might find useful:

Even some of the ostensibly forward-thinking companies out there are catching on.

This is, of course, highly-related to the knapsack-ness of the problem.

Congrats to you if you have a statistically significant win rate (or other KPI) with a certain segment that makes these calls a no-brainer. I’ve personally never seen it.