Bottoms-Up Books

A capacity-based approach to territory sizing.

Many larger sales organizations are already starting to think about planning for next year. The rest are making H2 adjustments.

In both cases, that means taking another look at territories. There are plenty of questions to ask about territories. But one question I personally get asked all the time1 is how big they should be. The answer, of course, isn’t completely straightforward.

Let’s dig in.

Reversing the pipeline

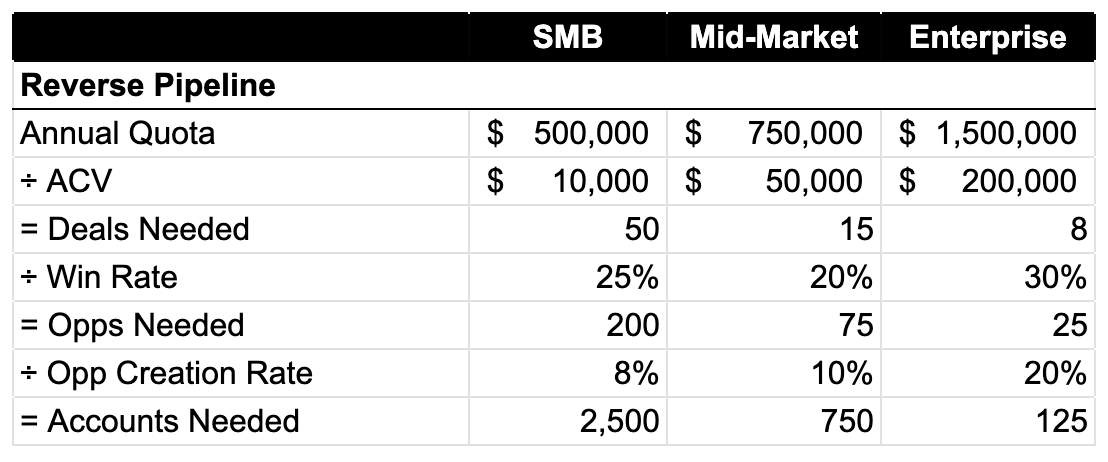

The typical way to approach static territory size is top-down. Given a desired quota, we do some “reverse pipeline” math to discover how many accounts a rep “needs” to have in their territory based on our conversion rate assumptions for ACV, win rate and prospecting efficiency.

It might look something like this for a new business team with 3 segments:

I’ve kept this example simple, but there are many options for this kind of analysis. For example, orgs with access to a reasonably sophisticated analytics team might choose to calculate revenue potential per account and use that instead of specific point estimates for ACV, win rate and OCR like the above.

However you slice it, the end result is the same: we start with the desired high-level outcome (“rep achieves quota”) and work backwards towards a territory structure that achieves it2.

This approach feels solid because it allows us to say we have the “right” number of accounts. We can tell a frustrated mid-market rep: “Stop complaining, Chad. We did the math and your territory’s fine! We gave you 1,000 accounts and you only need 750!”

What the rest of this article presupposes is… maybe Chad’s got a point?3

Considering capacity

First off, you 100% should start with the reverse pipeline analysis. Assuming the conversion rates are correct, a rep really will need to work that many accounts throughout the year.

What that approach doesn’t consider, though, is capacity. Capacity connects what you want to happen with what can happen.

Each rep only gets 24 hours every day4 which places a fundamental cap on how much work they can actually do. We can reduce the time required to perform each individual activity by using sales engagement platforms, parallel dialers, etc but there’s still a maximum in there somewhere.

So before we can be confident in territory sizing, we need to understand whether a rep can effectively work the number of accounts we believe need to go into a territory.

A brief caveat: I’m assuming we’re dealing with a primarily outbound motion. If your team is mostly inbound-driven, your bottleneck probably sits with demand generation instead of rep performance. And, if you’re lucky enough that your reps have more high-quality inbound than they can handle, you’re probably already hiring more reps.

I’m not suggesting you sit down with a rep and a stop watch to do a literal time study5, but I am suggesting that you think about the internal consistency of your own goals.

Here’s what I mean. Lots of teams define territories based on reverse pipeline math and then set an activity target of, say, 50 or 100 activities per day. What they rarely do is check whether that target is consistent with their territory design.

Connecting these pieces means translating activity targets to account coverage targets which requires a more nuanced understanding of what “coverage” looks like. You can define coverage with a statement like this:

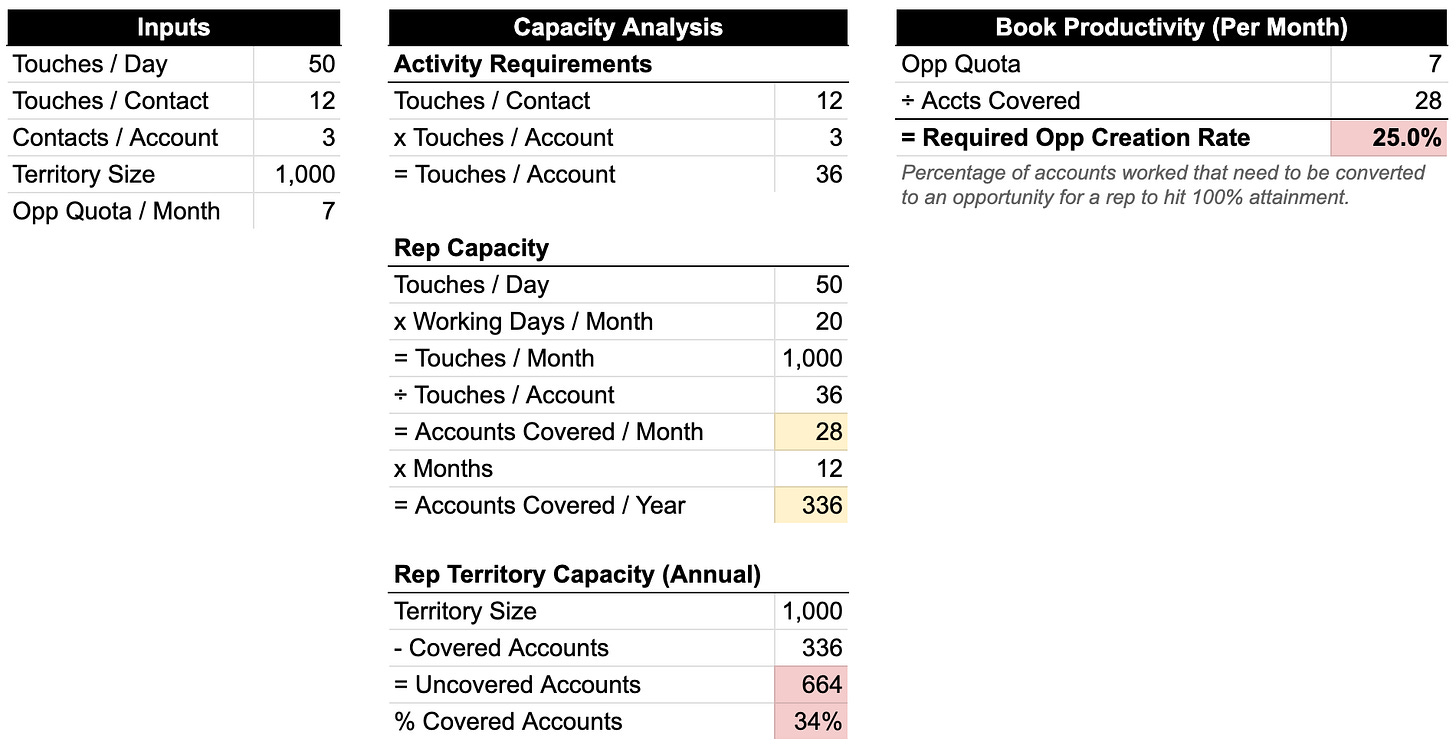

We expect reps to run a 12 touch sequence to 3 contacts over 30 days.

Now we know what coverage actually means for us and we can pair that with an activity target like 50 touches per day.

When we put it all together and do that math for Chad (our mid-market rep from the prior example), here’s what we get:

In the example above, we translated Chad’s pipeline requirements from 75 opportunities per year to 7 opportunities per month (it’s actually 75/12 = 6.25 but rounding up is usually a good idea in these scenarios).

We can clearly see that our capacity model and reverse pipeline territory size analysis are logically inconsistent:

Territory Size Mismatch - Chad can fully work 28 accounts per month which means he can only work 336 accounts per year, leaving 664 accounts untouched. Basically, he can only work 1/3rd of his territory.

Opportunity Conversion Rate Mismatch - In order to hit his pipeline generation goal of 7 opportunities / month, he’ll need to convert 25% of all the accounts he works into opportunities. The reverse pipeline math used a 10% OCR which means we’re far afield from the original model.

That’s not great. What do we do about it?

Finding a middle ground

We’ve got a clear example of the more prospects ≠ more pipeline phenomenon in action. We certainly can’t help Chad by giving him more accounts (even if that’s what he’s actually asking for) since he can only cover 1/3 of his territory as it stands.

We’ve got three choices:

Do More Activity - We tell Chad to just do more. If we double the touches per day to 100, we can double the number of accounts he can work to 2/3rds of his territory. This reduces his required opportunity creation rate by half (down to 12.5%) which gets us in the general neighborhood of the 10% we modeled for his territory.

Change Coverage Requirements - We could try shorter sequences and/or fewer contacts per account. Obviously if you can get by with 10 touches / contact and only 2 contacts / account on average that would be more efficient. (That math actually works out to 60% territory coverage and a 14% opportunity creation rate. Try it yourself in the spreadsheet.)

Smaller, Better Territories - Reduce the size of the territory down to the total number of accounts Chad can actually work over the course of the year, keeping only the highest quality accounts in the territory. Or better yet, only allocate the number of accounts Chad can actually work at any given point in time and dynamically assign new ones as he disqualifies them. Unlike the other two options, this one actually frees up accounts that could be put to good use by other reps (if you have the available capacity).

Most of the time, the answer is some combination of all three.

First, it may or may not be viable to ask Chad to simply do more. Sometimes reps just aren’t putting in the effort. Other times, doing more means quality suffers. It’s situation dependent.

Second, simply changing coverage requirements to make everyone feel better about territory size doesn’t work. All you’re doing is lowering your standards.

However, if you’ve tested changes like shorter sequences or fewer contacts and found that it doesn’t reduce opportunity creation rate, then go for it. Another related approach is to improve messaging to the point where more sequences can end early because you’re getting more responses. That will naturally drive down average sequence length.

Finally, revisit your territory size. The reverse pipeline math makes it pretty clear—the only way to materially reduce territory size is to improve conversion rates. That will probably require a trip back to ICP definitions, account qualification and account scoring. If you can find segments of accounts where you get meaningful efficiency improvements, then you can stock up smaller territories with better accounts.

Math > magic

I’ll wrap up here with a reminder. Don’t quit until the reverse pipeline approach and the capacity approach agree—without any magic improvements.

Magic improvements are changes to key drivers in the models (e.g. win rates, ACVs, activity levels, etc) that effectively boil down to: “I’m sure we’ll figure it out”.

It’s fine to make a few well-defined bets on doing things like improving conversion rates or reducing sequence length. Those bets must come with specific hypotheses and a clear plan. They’re not sure things, but they’re well thought out. You can still go too far here—stack too many “good” bets on top of each other and you’re back to magic.

So just remember, your territory sizes aren’t right until the math lines up. No magic allowed.

It’s an occupational hazard of running Gradient Works.

In this case I’m just working back to a number of accounts. A more nuanced design could be influenced by the total revenue potential of each individual account contained in the territory, along with other constraints. It’ll still need to cap the number of accounts for capacity reasons that will become obvious. I’ll try to return to this type of carving in a future article.

Based on personal experience, Chad will either say “there are so many accounts that I don’t know where to start” or “I don’t have enough good accounts to work.” We all know Chad is unlikely to ever say “my territory is perfect”. However, we owe it to Chad (and the company as a whole) to try to get this right.

But that might not be a bad idea. Senior leaders can often get pretty far away from the day-to-day rep experience. Maybe you used to crush the phones back in 2010 but much has changed since then.

Great article Hayes - thank you! I get the concept and am trying to figure out how including “signals” from prospects affects the math? Any suggestions there?