The Problem with Pods

The fatal flaws of the AE-BDR alignment used by 82% of sales teams.

Sales teams are a unique combination of people and technology that (hopefully) merge into a high-performing system. Unlike most systems that share those characteristics (e.g. manufacturing), sales teams are unique in that they give people wide leeway to operate creatively within the system.

That can make them especially confounding to optimize. If you’re trying to fix a bottleneck it’s hard to decide if the solution lies with people (training, teamwork, etc), technology (e.g. AI account research, parallel dialers), or how the system itself works (e.g. rethinking territories).

Sometimes the issue really is rep performance. Sometimes it really is solvable with new technology. However, I’ve found that the biggest breakthroughs usually come from questioning basic assumptions—those sales "laws of nature” that we take for granted. Of course we need 3x pipeline coverage. Of course we carve up geographic territories once a year. Of course reps have to make 100 calls to get a meeting. That’s just how it’s done.

Lately a particular sales “law” has been on my mind as I talk with sales teams about their pipeline challenges. Nearly everyone aligns BDRs to AE territories. Just take a look at this data from The Bridge Group’s 2025 Sales Development (SDR) Metrics & Comp Report:

This is Just How It’s Done. Questioning this is a little like questioning the laws of gravity. Or maybe, just maybe, it’s more like questioning the Aristotelian Physics of natural motion when an apple drops on your head.

[Editor’s Note: This newsletter article about BDRs should not be compared to the theory of gravity—arguably the most important breakthrough in the history of physics. About the only thing Isaac Newton and the author have in common is that they’ve both been under a fruit tree at least once. We regret the error.]

Despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, there are actually two basic configurations for aligning AEs and BDRs:

Pods - This is what 82% of sales teams prefer according to The Bridge Group. Each BDR is assigned to a specific set of territories and collaborates with the AEs who own those those territories to break into accounts.

Pools - BDRs are not aligned to specific territories. Their book of accounts is either a) pulled from across all territories or b) drawn from a pool of accounts that are not currently owned by an AE. When the BDR creates an opportunity it either a) goes to the owner of the territory it was sourced from or b) gets assigned to an AE using a balanced assignment mechanism1.

My goal with this article is to explain my strong preference for pools over pods—because the math shows that pods are likely to produce inferior outcomes in the real world.

But first, let’s look at why pods have overwhelmingly won the popularity contest.

Pods: 82% of sales teams can’t be wrong. Right?

The goal of the pod model is to make the most of a static territory by having the AE and BDR collaborate. The BDR’s job is “breaking into” new accounts while the AE’s principle job is closing. I say “principle” because most teams expect AEs to do some of their own outbound alongside the BDR.

Here’s how it usually works:

Carve up (semi-equitable) territories by attempting to balance revenue potential.

Assign an AE to a territory.

Establish a BDR:AE ratio (e.g. 1:2). Each BDR supports that many AE territories.

The BDR and AE collaborate to cover accounts (with the AE guiding “strategy”).

The BDR produces pipeline and the AE closes.

In principle (there’s that word again), there’s a lot to love about this model:

Coverage - The AE and BDR combined can fully engage the territory.

Specialization - AEs work key accounts and close deals; BDRs open doors.

Collaboration - BDRs and AEs work together on smart ways to engage accounts.

Mentorship - BDRs learn from a more tenured AE so they can become closers.

Career Path - BDRs who do well get promoted to AE.

But here’s the big problem—the vast majority of these benefits don’t materialize in practice.

First, most of the benefits of the model hinge on AEs being good partners and mentors to their BDRs. Yes, this does sometimes happen. But very often the BDRs end up as EAs to the AEs.

Second, the bifurcation of accountability between BDRs and AEs creates plenty of challenges.

Because both the AEs and BDRs share coverage responsibilities, it’s easy to pass the buck. I’ve seen many AEs who don’t do much proactive outbound point the finger at the BDR when pipeline is low. But it gets even trickier.

BDRs work with the AE in a semi-subordinate relationship but don’t report to the AE. Sometimes the BDRs don’t even report into the sales team at all. This means a BDR is likely to hear one thing from the AE and another thing from their manager. This would be super challenging for an experienced employee and we all know BDRs are anything but. All of this can be managed, but it’s really, really tough to get right.

Third, the promotion track is broken. In The Bridge Group’s data, only 16% of BDRs got promotions in 2024, down from 34% in in 2020. While most companies (71%) offer a BDR-to-AE career path, that number is down quite a bit from 80% in 2023. Clearly something about the mentorship and career path elements of these pods isn’t playing out as intended.

Finally, and most damning, the actual revenue-generation math doesn’t work nearly as well as you think it would. So let’s spend more time there.

Modeling pod performance

As always, I like to think through the problem with a model. I’ll keep the numbers relatively simple, but close to something you might find in the real world.

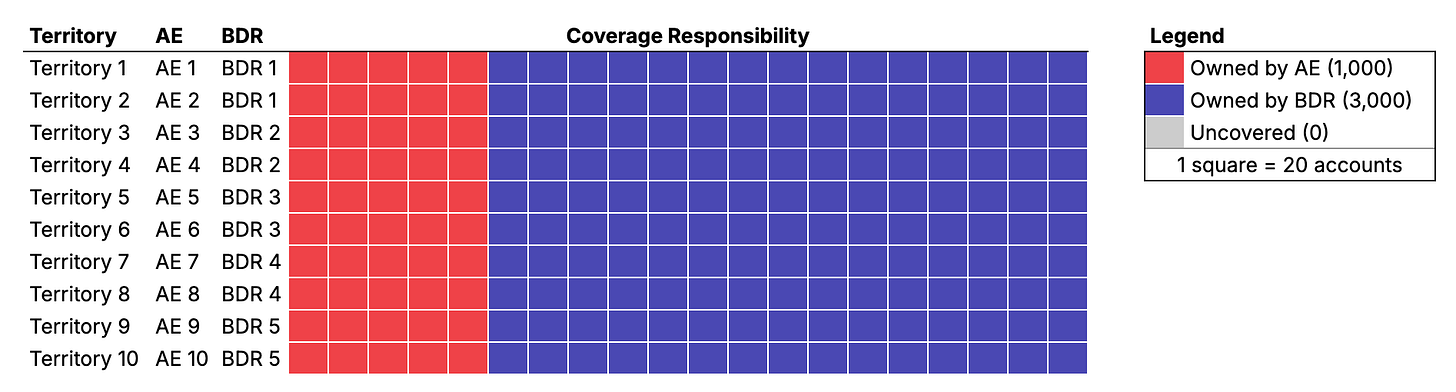

Imagine a team with 10 territories, each of which has 400 accounts. Of course, we assign an AE to each territory. Now the AE has a lot of work to do running sales cycles and such so they can only be responsible for prospecting 100 accounts in their territory personally. They each need help with the other 300. So in total, the 10 AEs will cover 1,000 accounts but that leaves 3,000 prospects that nobody’s engaging.

So, we do the logical thing—hire some BDRs. We estimate a BDR can cover 600 accounts. We have 3,000 accounts to cover, so we decide to hire 5 BDRs, giving us a tidy 1:2 BDR to AE ratio. We decide to be like 82% of sales teams and pod them up with AEs so that each BDR supports two territories.

Here’s a little visualization so you can see it all at once:

Pretty simple. We’ve got 4,000 accounts to cover across our 10 territories. The AEs are responsible for 1,000 of them and the BDRs get the other 3,000—clear responsibility, full coverage, can’t lose.

Not so fast.

How pods unevenly distribute pain

The trouble starts, as most troubles do, when we start considering the details. Let’s start by adding one critical wrinkle from the real world: BDR attrition.

We all know attrition will happen and we build it into our plans. Let’s include it in our model here.

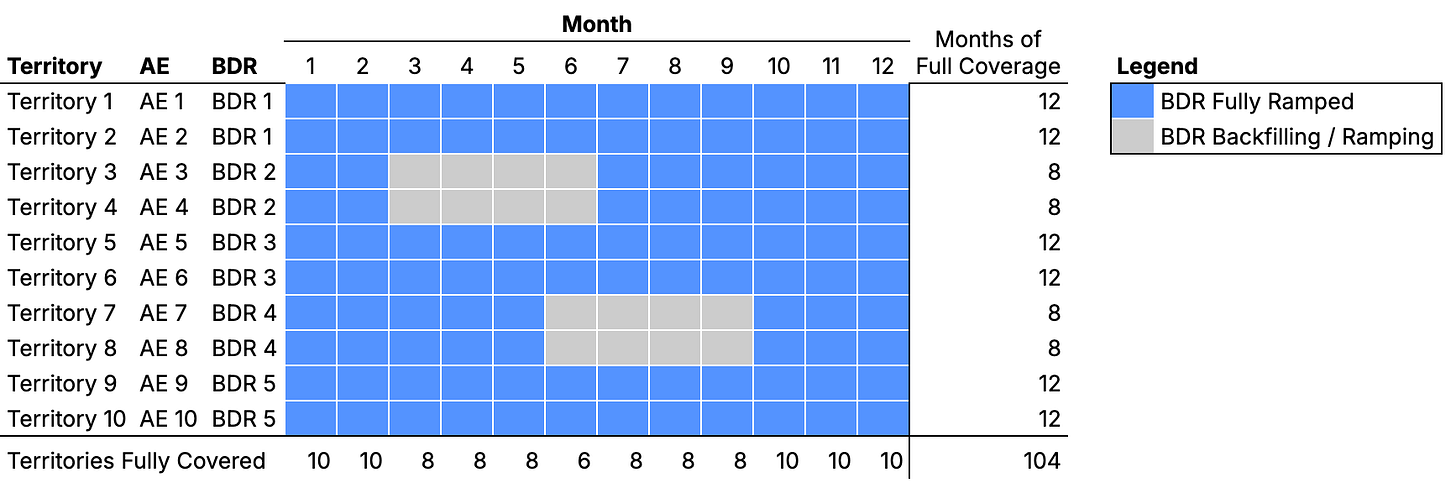

The Bridge Group pegs annual BDR attrition at 40% and ramp time at 3 months, so we’ll roll with those numbers2. In our model, this means we can expect to lose 2 of our 5 BDRs at some point during the year. Even assuming we have an always-on hiring pipeline and can immediately replace any BDR within a month, we’re still looking at 4 territories without full coverage for 4 months during the year.

That might look something like this (if BDR 2 leaves in Month 3 and BDR 4 leaves in Month 6):

If we think of ourselves as having 120 “coverage months” across our 10 territories each year, we’ll have full coverage only 104 of those months (104/120 = 87%).

Maybe that’s not the end of the world for the overall plan, but the pain isn’t evenly distributed. Whenever one BDR leaves, they leave two AEs high-and-dry on pipeline support. Each of these reps now only has full territory coverage for 8 of 12 months (67% of the year) in their territory, while everyone else has 100%. Rough.

BDR attrition is a fact of life, so the pod model inherently means we’re condemning some of our AEs to less pipeline support than their peers.

How pods impact pipeline

Let’s go one level deeper and look at territory composition. After all, all accounts in a territory aren’t created equal.

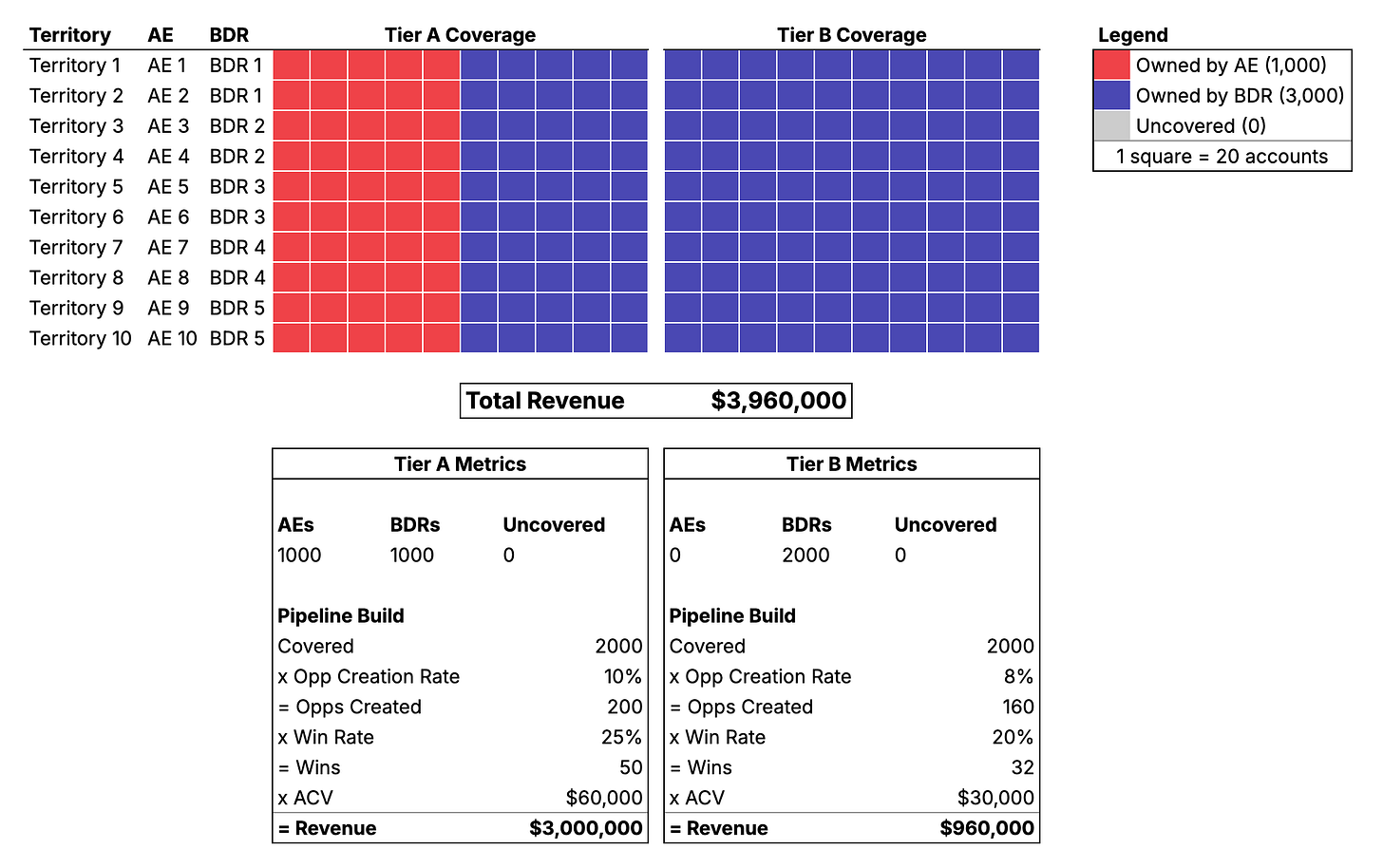

Let’s assume that each territory comprises some Tier A and some Tier B accounts. Tier As are the best accounts—they have our highest opportunity creation rates, win rates and ACVS. They’re a little scarce so we can’t just have territories that are 100% Tier A. We have 2,000 of them total so we put 200 in each territory.

Tier Bs are good—just not as good as the Tier As3. We use them to fill out the remaining 200 accounts in each territory.

Since our AEs only have capacity to work 100 accounts each, they get 100 Tier As from their territory. That leaves the other 100 Tiers As and 200 Tier Bs for the BDR.

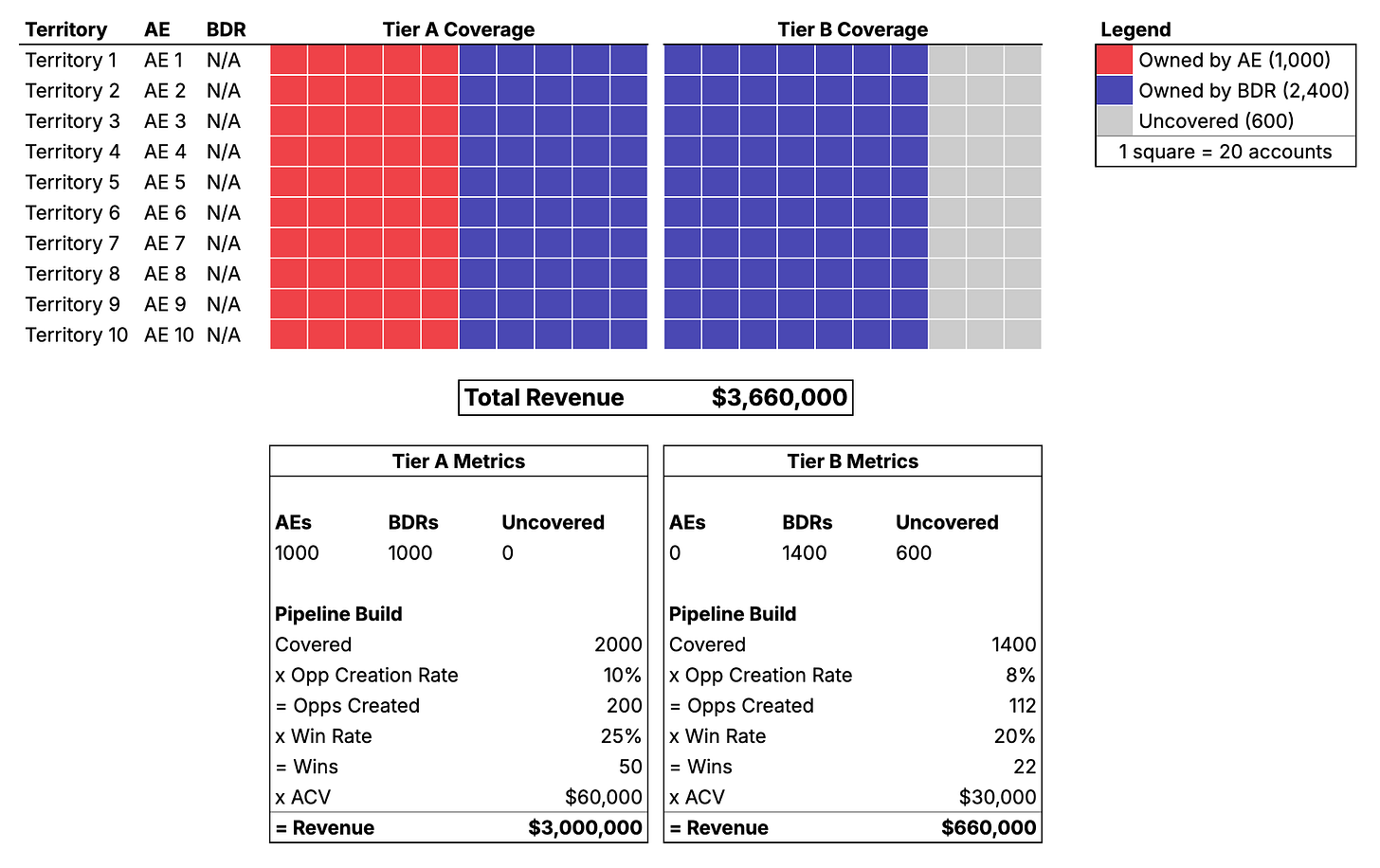

Here’s an expanded visualization that also includes some conversion assumptions to describe how much revenue we could generate from this kind of setup.

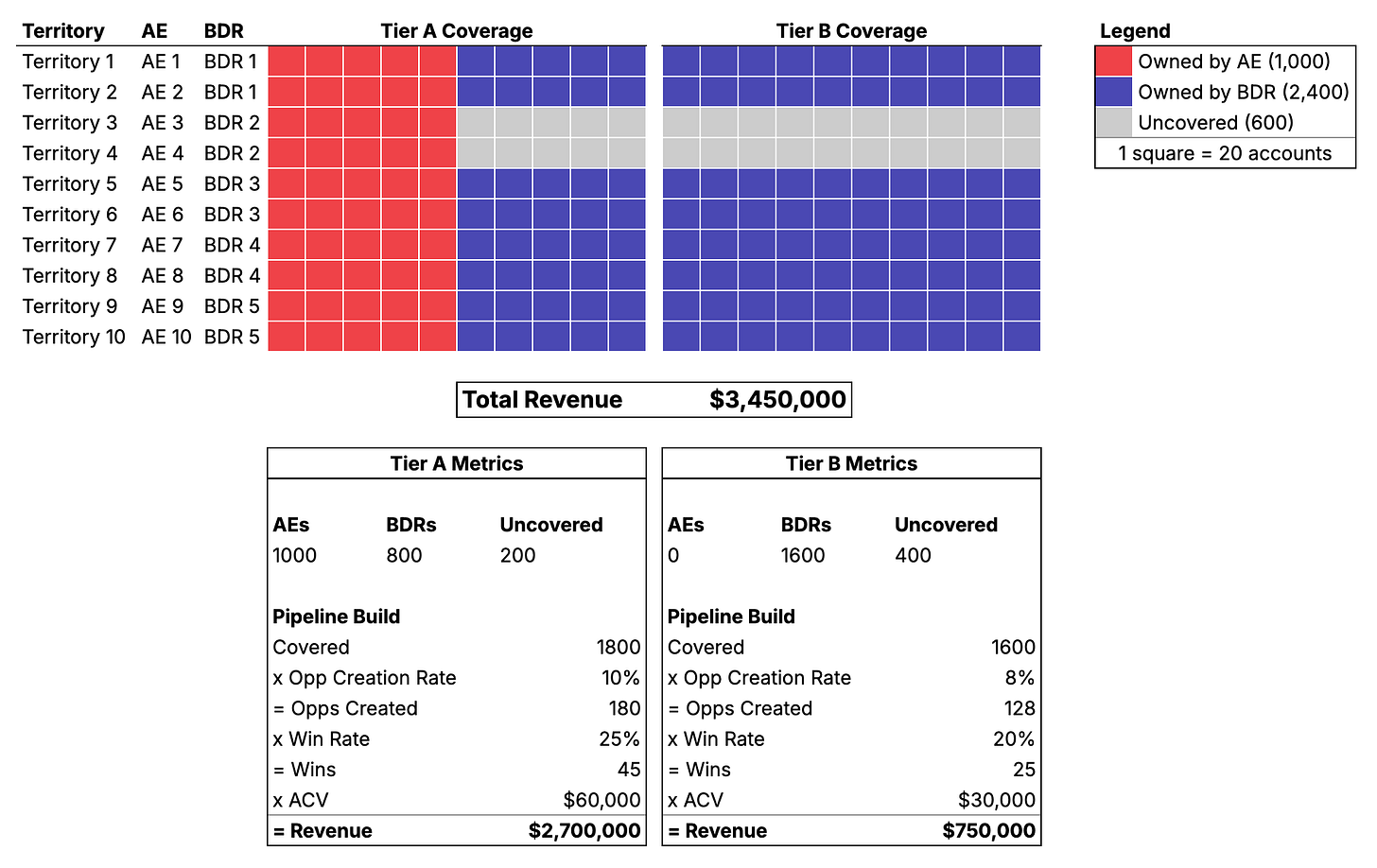

Now, let’s consider rep attrition again and remove a BDR from the equation. For simplicity’s sake I’m not going to try to combine the the time-based attrition calculation above, instead I’ll just look at the drop in capacity if we go down one rep for a whole year (this isn’t totally valid—in a 40% attrition model, we’re likely to spend roughly as much time down a rep as we are at full capacity—but it works for comparison purposes).

Here’s what losing a BDR looks like:

We see a drop of $510k in expected revenue compared to the full coverage scenario. Most of this loss ($300k) is driven by the uncovered 200 Tier As whereas the remaining $210k comes from the 400 uncovered Tier Bs. We pay a big price for those uncovered Tier As even though we have other BDRs who are using their capacity to cover Tier Bs in their assigned territories.

And that’s where pools come in.

How pools protect pipeline

I’ve spent most of this article talking about pods without talking too much about how pools actually work.

The general idea is pretty simple. BDRs aren’t directly aligned to any single AE territory. Instead of having individual pods of AE-BDR pairings, you have two teams: the AEs and the BDRs.

The job of the BDR team is to help produce pipeline for the AE team—not any individual AE. As I mentioned above there are usually two basic ways this plays out: one with more traditional territories and one with dynamic books.

Traditional Territories - AEs are assigned territories just like the pod model. In this case, they claim ownership of a set of accounts in those territories that they’re solely responsible for outbounding to. The rest of the unassigned accounts become part of the pool of accounts that the BDR team works. A single BDR’s efforts will be spread out across territories.

Dynamic Books - AEs and BDRs both work focused books of accounts from a single pool. There is no shared ownership. When a BDR sets a meeting, that account is assigned to an AE who has capacity to run that sales cycle.

Let’s revisit the attributes of the pod model and see how they change for the pool model:

Coverage - AE and BDR teams combine to cover all accounts.

Specialization - Same as pods. AEs work key accounts and close deals; BDRs open doors.

Collaboration - AE and BDR teams collaborate together to run plays.

Mentorship - BDRs learn from more senior BDRs and BDR managers. They also get plenty of exposure to AEs, they just don’t directly answer to AEs for coverage strategy.

Career Path - Same as pods. BDRs who do well get promoted to AE.

Compared to the pod model, this model relies less on individual-level relationships and more on team-level efforts. I think this is generally a better bet as it relies on alignment between team leaders who are better equipped for that than ICs.

It also has less of the shared responsibility and dotted-line type reporting of the pod model—each rep is responsible for their specific book and each BDR answers to one single manager.

One area where pools may be inferior to a high-functioning pod model is that BDRs may end up with less 1:1 time with more senior closers. This can be mitigated with training or even specific mentorship programs. And, as we’ve already seen, pod-style mentorship isn’t leading to strong BDR promotion rates.

All these are reasons to prefer pools over pods. However, the biggest reason in my mind is that pools create more equitable outcomes for all reps while actually being more efficient at producing pipeline. Let’s look at the math.

Pools are resilient to attrition

BDR attrition brings out the biggest problems with pods. When a BDR leaves in a pod model, they take specific territories down with them which means some AEs suffer disproportionately.

Those uncovered territories also include high-value accounts that get no engagement while lower-value accounts continue to get engagement in other territories. In other words, quota capacity gets misallocated when it’s constrained.

The beauty of pools is that if you lose a BDR, you can reconfigure your coverage to make sure that the best accounts remain covered and no individual AE loses pipeline support completely.

Here’s what the lost BDR scenario can look like under the pool model:

Losing one BDR means we’ve lost the capacity to cover 600 accounts. Instead of keeping an entire territory uncovered, we re-assign accounts such that all Tier As remain covered and we take the 600 account “hit” in the form of Tier Bs.

This simple change reduces the revenue loss from losing a BDR from $510k in the pod model to $300k in the pool model—all because we continue covering all the high value accounts. Further, this $300k hit is spread across all the AEs instead of being concentrated in 2 specific territories.

That’s a material win for the pool model.

Wrapping up

Perhaps you’re running an enterprise motion with a handful of named accounts operating on 18-month sales cycles. In that case, your AE and BDR may both be “walking the halls” for months to win these key accounts. Or maybe your team is great at mentoring and your podded BDRs are routinely graduating to be amazing closers. If the pod model’s working for your reps, let ‘em cook.

But if you’re part of the 82% of teams that pod your AEs and BDRs and you’re also falling short of your pipeline goals while dealing with high BDR attrition, take a hard look at doing things another way.

Maybe those “natural laws” we take for granted aren’t laws after all and a change to the system can unlock an entirely new level of performance—no apple trees required.

Like round-robin or load-balancing.

See slides 23 and 20, respectively, in their 2025 report.

And the less said about Tier Cs the better.

What do you think about larger pods -- like a pod of, say, 3 AEs and 3 BDRs?

I realize that in smaller companies, those numbers may represent the entire sales team. :-)

But in larger orgs, I've seen this kind of pod model avoid many of the pitfalls you described.